Who is Elisa Motterle, etiquette expert

Etiquette, bon ton, table protocol. More simply, good manners, those capable of "saving the world", or at least giving it back a pinch of good manners. Words are important but never as in this case, paradoxically, does the content matter more than the form: far from snobbery, Elisa Motterle continues to be the spokesperson for good manners. She is an expert connoisseur of etiquette capable of applying it and adapting it to modern times. Rejuvenate it, as she writes in her Instagram bio, liked by over 80,000 followers. In addition to the social channel there is a website, the work of a consultant and that of a teacher, with courses and workshops of all kinds, many of which are dedicated precisely to the table "after all, that is where the first rules of etiquette were born." Before that, however, she too was a student at the International Etiquette and Protocol Academy in London, a path undertaken after years in the luxury sector, from Yoox to Kering, passing through Armani, "I was in charge of the commercial and digital part. Over time, I then began to take care of projects related to the customer experience."

The training courses

It is precisely during these works that she realised the importance of the human and empathic side in communication. Which for Elisa was precisely the heart of etiquette, "a way of acting that looks to others, before looking at ourselves." Passionate about good manners since childhood, Elisa had already attended courses with the National Association of Public Bodies Ceremonialists and then decided to specialise in London, where she learned the art of bon ton understood as "a personal strengthening tool," useful in relationships with others: "If you know the rules you know how and when to apply them based on the context." Today Elisa works with various companies and continues to study, "Last year I took a butler course," in addition to being very present on Instagram, where she constantly answers questions from followers. It is through her social networks that she manages to make her philosophy understood, that she refuses any divisive attitude, "etiquette, on the contrary, serves to put everyone at ease."

Good table manners: conviviality

Once the concept of good manners has been clarified, let's get to the table. There are many "rules" to follow, the most varied contexts to be considered. What we should never forget, however, is a principle that is as simple as it is often overlooked: conviviality. "Today it is often not even possible to have lunch with colleagues but, in the event that this happens, it is good to keep in mind some precautions." Like waiting for everyone to be seated, starting to eat together and keeping pace with the others, "if you choose to share a meal, it is good to show that you want to do so." Ditto in the family, especially when there are children, "who often drive us crazy, I know, but we should always try to keep the conversation going."

The rules at the table and the birth of the fork

We then come to "basic" rules, the classic ones that almost all of us know. There is a reason we still know them by heart today, and often it has nothing to do with good manners. Indeed, many of these habits arise out of necessity, out of pure common sense even before gallantry. Do not rest your elbows on the table, for example, a rule born in the Middle Ages when the tables were not fixed but mounted with trestles: "The guests all sat on the same side to be able to enjoy the banquet together. If they had leaned on it with their elbows, they would have unbalanced the table." Another aspect to remember when eating: do not gesticulate and do not point cutlery at other diners. But let's analyse the differences between the various pieces of cutlery: the knife belonged to the rich, of those who could afford meat, and in the Renaissance it was worn on the belt. The fork, on the other hand, only began to take hold in those years: it already existed before, brought to Europe around the year 1000 thanks to a Byzantine princess married to the Doge of Venice, but was soon banned because it resembled the devil's pitchfork. In the sixteenth century, with the spread of pasta, it returned to the table, to remain there together with the knife and spoon, "the cutlery of the poor, who could only afford soups."

The birth of table etiquette

It was from the eighteenth century that the rules of the table began to take shape, especially in the French courts and in particular with the Sun King, who made them official to the point of making them a powerful propaganda weapon. Even before, however, banquets in Italy were real staged events, sumptuous dinners set up to demonstrate the power of the lord, "Leonardo Da Vicini was called by the Sforzas precisely as a set designer for the banquets." And speaking of Da Vinci… on the occasion of his visit to Milan, the genius of the Italian Renaissance perfected an invention that is still fundamental today: the napkin. An element that later became of daily use, the first one that a guest picks up during a meal. Traditionally, the hostess is the last to sit down, the last to be served but the first to take the napkin: "This is the signal that starts the meal. We know, don't we, that we don't say bon appétit?"

Is etiquette sexist?

A very large chapter in etiquette is also reserved for women. Technically, when a lady gets up from the table, the others can also make the same gesture, "however, we are talking about obsolete rules that are no longer applicable." As well as that of wine: "the kiss on the lips was born thanks to the Romans who had to check if the wife had been drinking." Superfluous but perhaps necessary to specify that etiquette is not law and no one expects a woman to comply with such antiquated rules, "I love good wine: I would be the first to be banned from any event!" To clarify, if still needed: yes, etiquette has a form of internalised sexism, sometimes benevolent but still present. Can't feminism and bon ton therefore go hand in hand? As always, a good dose of flexibility should be maintained: it is clear that we are talking about rules established at a time when gender equality was still a distant concept. For this reason it is good to follow the advice of people like Elisa, who is able to interpret and re-adapt etiquette to the times.

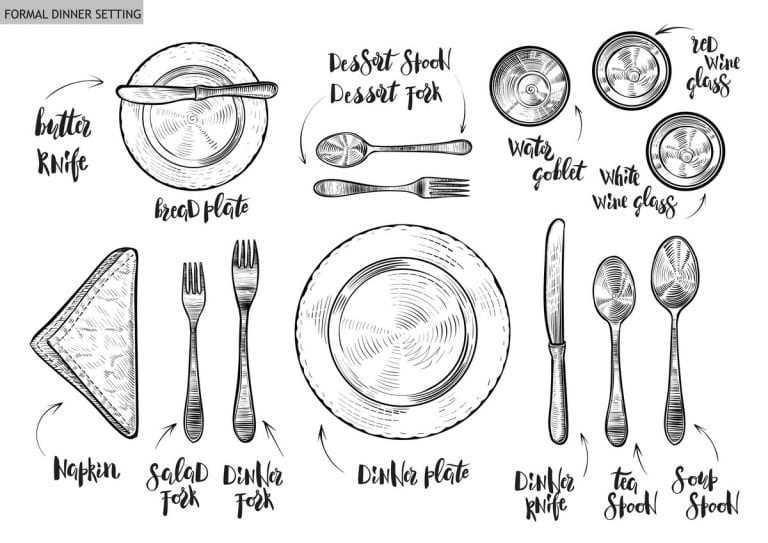

How to set the table

We come, now, to table setting, "increasingly subject to fashions and trends thanks to social networks." There is no unique style, restaurants usually take up the English model: spoon and knife on the right, fork on the left, glass in the upper right, plate in the centre and forks above for dessert, while the saucer in the upper left is for bread. However, restaurateurs do not know what we will order: it is always better to keep only what is necessary at home. Plus, "anyone who has seen Titanic or Pretty Woman knows: always start from the outside and work your way in!"

Who pays at the restaurant?

One of the most age-old questions ever, at the centre of debate between couples, friends and colleagues: who pays the bill at the restaurant? Simply, the person who invites. "Chivalry is a delicate subject, which changes according to the culture. In some countries waiters ask if you prefer a single or separate bill, while in Italy it is still often brought automatically to the man." Naturally, the problem arises for every type of couple and not only for love, but also for work. To clarify any doubts, just remember that "whoever invites, pays." And it is good to keep in mind that, regardless of the dinner, you can reciprocate afterwards, "by treating a taxi ride, movie tickets or a drink."

Do we really need etiquette?

Ancient etiquette, modern etiquette. Good manners evolve with us and continue to come in handy: "There was no smart working, Zoom or Clubhouse etiquette before the pandemic. And yet, now even in these contexts there are rules that beg to be respected." So is etiquette still useful? Perhaps today even more than yesterday, now that informality has taken hold in any area, even ceremonies: "Sometimes I receive messages from people invited to a wedding via WhatsApp. Or others to which unclear invitations have been sent, such as 'if you can, stop by for the birthday'." The intentions, more often than not, are good: you don't want to bind guests and you don't want to make them uncomfortable with any gifts. This de-formalisation, however, risks confusing those who receive the invitation "and not making people feel all important."

More attention to others, their needs and their feelings. "Less individualism, more collectivity, as in Eastern societies." With a dusting off of good manners, applied with intelligence. Using etiquette as a tool in our favour, understood as an "ecology of relationships: just as we have realised that we cannot continue to produce waste, sooner or later we should come to terms with the fact that we have to stop thinking only of ourselves."

by Michela Becchi

Meloni: "Tariffs? If necessary, there will be consequences. Heavy impact on agri-food sector"

Meloni: "Tariffs? If necessary, there will be consequences. Heavy impact on agri-food sector" The Government honours the greats of Italian cuisine, from Bottura to Pepe. Massari: "Thank you, Meloni, the only one who listened to us"

The Government honours the greats of Italian cuisine, from Bottura to Pepe. Massari: "Thank you, Meloni, the only one who listened to us" "We must promote a cuisine that is not just for the few." Interview with Massimo Bottura

"We must promote a cuisine that is not just for the few." Interview with Massimo Bottura Wine was a drink of the people as early as the Early Bronze Age. A study disproves the ancient elitism of Bacchus’ nectar

Wine was a drink of the people as early as the Early Bronze Age. A study disproves the ancient elitism of Bacchus’ nectar "From 2nd April, US tariffs between 10% and 25% on wine as well." The announcement from the Wine Trade Alliance

"From 2nd April, US tariffs between 10% and 25% on wine as well." The announcement from the Wine Trade Alliance