by Rosaria Castaldo

The meeting point is in Perugia’s historic centre, at the corner of Via dei Cartolari and Via Alessi, in front of the elegant Palazzo Ansidei di Catrano. One’s imagination immediately drifts to the luxurious life of Luisa Spagnoli, a pioneering entrepreneur in the food and fashion sectors. She became wealthy, but she started in the basement of that very same building, at number 23. A nondescript iron gate opens onto a short, uneven ramp. A glass and iron door was the entrance where over 50 workers and managers spread out over the four floors below street level. By the end of the Great War, she employed more than a hundred workers, almost all women. Welcome to the first factory of the Società Perugina per la fabbricazione dei confetti (Perugina Company for the production of sugared almonds), which closed in 1922 to move to larger premises. Since then, the basement has not been rented out again. Nothing has been altered over the years, and only a few visitors have had the privilege of entering this magical place. It seems unbelievable.

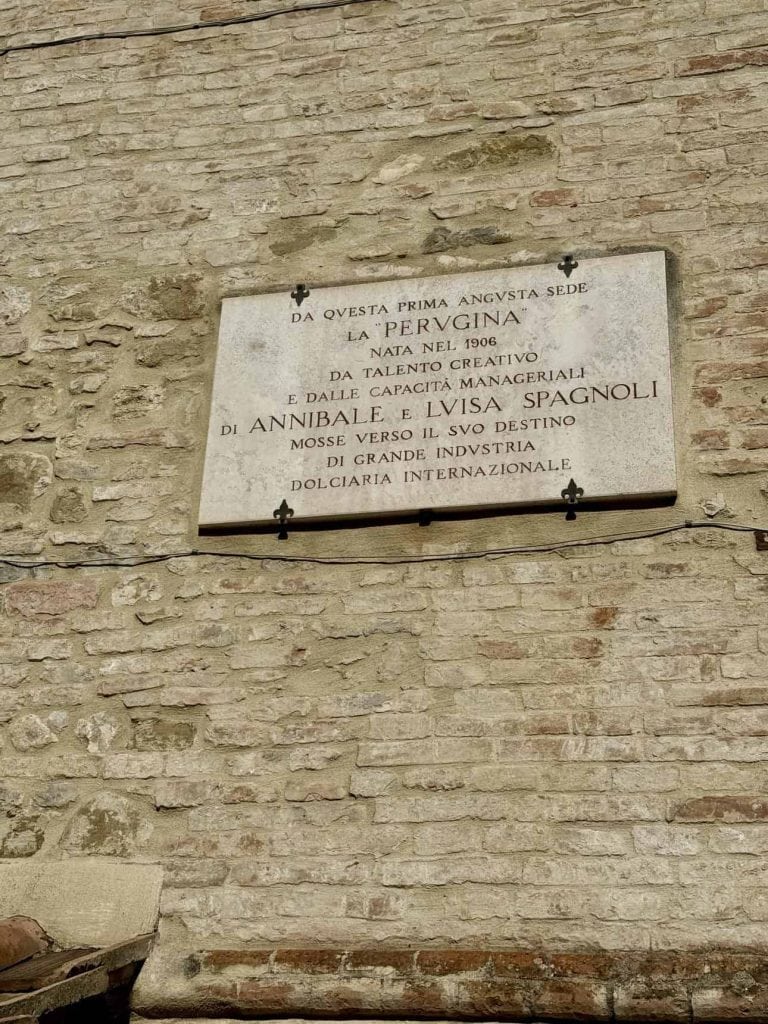

Today, we can learn about the human story behind it through a journey back in time offered by a brief but intense tour. It’s a path through the public and private life of a woman who defied social and moral conventions, dedicating her life to overcoming poverty and, with her brilliance and altruism, creating the first corporate welfare system to support working women and the vulnerable. Luisa was born into extreme poverty on the street opposite the workshop, at Via dei Cartolari 13, in 1877. From a young age, she worked to help her widowed mother raise her siblings. But if you’re looking for a commemorative plaque on the wall of the building where she was born or at the workshop entrance, you’ll be disappointed. These places, so crucial to the personal and professional growth of the enterprising young woman, remain completely anonymous.

The story

Luisa Sargentini married musician Annibale Spagnoli at 21, with whom she had three children. It was a love marriage that also laid the groundwork for a business partnership. Together, in the early 20th century, they took over the basements on Via Alessi, where they initially made and sold jams and sugared almonds.

Some of the kitchens remain intact, as do the marble countertops where female workers packaged sweets, which were then shipped to increasingly distant locations. This expansion was made possible by Giovanni Buitoni, who joined the company, bringing administrative expertise and capital to transform the confectionery workshop into a chocolate factory—just as Luisa had envisioned to address wartime sugar shortages. Even today, some tools and tin containers from the early 20th century are still visible. Some items have been reproduced or added later, but the energy coursing through those damp and decaying rooms, amidst pieces of rusty machinery—cutting-edge at the time—propped-up offices, and blackened ovens, is palpable. It’s almost as if you can glimpse the elegant woman, wrapped in one of her angora wool shawls (her invention), moving among the workbenches to offer advice and create new products. It’s in these very rooms, according to historical gossip, that secret notes, first as service orders and later as love messages, were exchanged between Luisa and Giovanni. These secret notes inspired the love phrases tucked into the Baci chocolates, one of the many brilliant ideas conceived by the entrepreneur. However, the name of the now-iconic chocolate—designed to repurpose leftover hazelnuts from production—was Giovanni’s idea. At its launch in 1922, in Perugina’s first shop on the elegant Corso Vannucci (now a branch of an eyewear brand), Luisa presented the chocolate as the Cazzotto (punch). Following Buitoni’s suggestion, it became the Bacio Perugina, elegant in its iconic silver wrapper.

Luisa’s husband eventually left the business due to a nervous breakdown, or perhaps because of rumours about his wife’s relationship with the younger Buitoni. At the time, a wife’s infidelity was unacceptable, and an affair with a man 14 years her junior was particularly scandalous. Despite this, Luisa and Giovanni continued their relationship discreetly and consistently until her death, achieving success after success, including the Fondente Luisa, the legendary Rossana candy, and the Banana. Every initiative launched by the entrepreneur was a success, from angora wool garments to the first amusement park, nurseries, and canteens—but that’s another story.

The Future of Perugian Chocolate

Exploring the dark rooms with uneven floors, among fragments of old furniture and crumbling ovens, a rear passageway leads outside. It was here that raw materials were brought in and finished products were sent out across Italy. The view overlooks Perugia’s old, now-disused market. The factory had a perfect logistical position until Buitoni began exporting abroad, prompting a move to a large facility near the Fontivegge railway station. At the corner of the rear street, one finally finds a marble plaque commemorating the entrepreneur, who died prematurely at 58 in Paris after a long illness. Giovanni did everything to save her, never leaving her side. And it is from the rear of the first workshop—a symbolic place—that the future of the food of the gods is reborn.

Luisa would be delighted to know that her vision has evolved into a tourism and commercial industry around chocolate, positioning Perugia as a global reference for chocolate. It was recently announced that the Città del Cioccolato (City of Chocolate) will open in the former covered market—a 2,800-square-metre experiential museum dedicated to cocoa in all its forms. This idea, developed by Destinazione Cioccolato, extends Eurochocolate, the international chocolate festival that has drawn hundreds of thousands of visitors to Perugia for 30 years. The initiative’s success is bolstered by the results of an equity crowdfunding campaign launched on Mamacrowd, which raised €1 million to complement the approximately €6 million allocated for the mega-project. An exceptional economic outcome and strong public engagement confirm the enduring appeal of Perugian chocolate, the world’s chocolate capital.

The 11 best-value Dolcetto wines from the Langhe

The 11 best-value Dolcetto wines from the Langhe Coratina party in Paris: the power of Puglia in a drop of oil

Coratina party in Paris: the power of Puglia in a drop of oil In a historic building in Genoa hides a top cocktail bar

In a historic building in Genoa hides a top cocktail bar Giancarlo Perbellini: “The future? Less oppressive restaurants. If we don’t make young people fall in love with this job, we might as well close”

Giancarlo Perbellini: “The future? Less oppressive restaurants. If we don’t make young people fall in love with this job, we might as well close” The great oils of Puglia on display in Düsseldorf

The great oils of Puglia on display in Düsseldorf