Would you fancy a Pinot Noir from Scania or a Bronner from Småland? Or perhaps a sparkling wine from the Andes or a Regent from the Langhe? Don't worry! You haven’t unknowingly become a character in a dystopian series about the winemaking future. However, this is a reality we might face in the future. Climate change is reshaping the global wine landscape, pushing vineyards to higher altitudes and northern latitudes. Rising temperatures and changing weather patterns present significant challenges for many historically renowned wine regions.

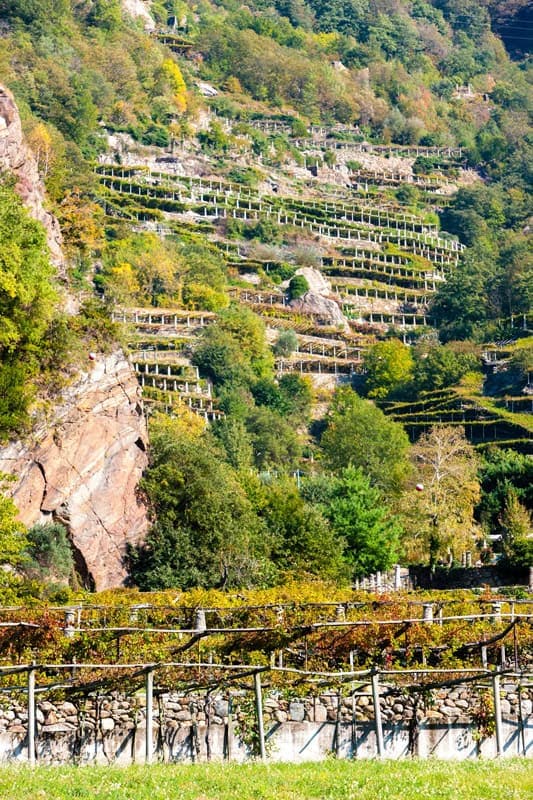

Vineyards in Valle d'Aosta. Opening image: the vineyard of Immacolata Pedace, in the Sila region.

70% of vineyards at risk

A study by the Universities of Bordeaux, Palermo, and Burgundy has revealed that over 70% of current wine regions could become unsuitable by the end of the century due to climate change. Countries bordering the Mediterranean, such as Italy (particularly Sicily and Sardinia), Spain, and Greece, are at the highest risk, despite their millennia-old winemaking traditions. However, new areas at higher altitudes and latitudes could become suitable for viticulture.

Regions like southern England and northern France have recently emerged as new wine-producing areas. Even southern Sweden, where temperatures have risen by almost double the global average since the late 19th century, has seen the planting of new vineyards, growing from four to forty in just a decade.

Adaptation strategies: going higher

For years, the wine world has been developing adaptation strategies, such as selecting drought-resistant grape varieties and rootstocks and adopting growing systems that delay ripening. The search for areas where rising temperatures and extended droughts can be mitigated is leading not only to a northward shift but also to higher altitudes. Although mountain wines are not entirely new, either in Italy or elsewhere, moving uphill might be a viable solution in some contexts.

"There are areas where high-altitude winemaking has been practiced successfully for a long time, like Valtellina, Valle d’Aosta, and Mount Etna, where excellent wines are made around 1,000 meters," explains Michele Lorenzetti, a winemaker and biologist consulting for several biodynamic wineries.

Lorenzetti adds, "What’s more concerning than rising temperatures are the extreme weather events: frost, heavy rainfall concentrated over several days in unusual seasons, heatwaves, and prolonged droughts."

High-altitude production: pros and cons

According to Lorenzetti, "It all depends on the winemaking goals, the grape varieties, and the interplay between altitude and latitude. While mountain viticulture has the advantage of delaying the vine's growth phases, protecting it from frost and extreme weather, there can be challenges in grape ripening. If ripening is difficult and alcohol levels remain low, the resulting wines may be light, low in alcohol, and high in acidity – suitable for easy-drinking wines or sparkling wine bases."

A notable example of high-altitude experimentation is the Ciu Ciu winery in Marche, which produces classic method sparkling wines using Pecorino grapes grown between 600 and 700 meters, an altitude that enhances its acidity, which is less pronounced in lower-lying areas.

Experiments in Calabria and on Etna

In Italy, there are vineyards over 1,000 meters, such as those at the foot of Mont Blanc in Valle d’Aosta, where Cave Mont Blanc has created a high-altitude winery to vinify Prié Blanc grapes at 2,000 meters.

In Calabria, at Cava di Melis in the heart of the Sila National Park, Immacolata Pedace cultivates international varieties like Chardonnay, Pinot Blanc, and Gewürztraminer at 1,300 meters. This project, launched in 2006, is now one of the highest vineyards in Europe.

On Etna, Sciara is an exemplary case of high-altitude viticulture. Stef Yim, an Asian-American winemaker, grows Grenache at 1,200 meters and has planted 4,500 red grapevines on the northwestern slopes of the volcano at 1,500 meters, potentially breaking records for Europe’s highest red vineyard.

The vineyards of Visperterminen in Switzerland, one of the highest wine-growing areas in Europe.

The "povocation": grapes at 3,600 meters

A bold experiment by Roberto Cipresso, one of Italy’s most talented winemakers, pushes the boundaries even further. In addition to producing Malbec at 2,200 meters in Argentina, Cipresso planted Riesling, Chardonnay, and Pinot Noir in Moray, near Cusco, Peru, at 3,660 meters, creating what is considered the highest vineyard in the world.

DOC and DOCG boundaries in flux: debates and controversies

In Italy, the need to adapt to new climatic conditions has sparked debates over expanding DOC boundaries to higher altitudes or areas previously excluded from production rules.

For example, in the Barolo region, the possibility of including higher-altitude areas to maintain quality has caused concern among traditional producers. Similarly, on Etna, the push for higher-altitude vineyards has divided local producers, with younger ones seeing the opportunity to preserve freshness and acidity, while others fear it could alter the distinctiveness of Etna wines.

The vineyard where Nicola Biasi's Vin de la Neu is produced, a leader of the "Resistenti" network cultivating Piwi grapes.

New grape varieties: resistant grapes

“Perhaps identity can be preserved by breaking the link between grape variety and territory. How? By opening up the regulations to the use of new grape varieties that may be better suited to the changing climate and perhaps better reflect the territory today,” suggests Nicola Biasi, a winemaker specialising in resistant grape varieties and owner of Vin de la Neu, which produces around a thousand bottles a year from Johanniter grapes grown in vineyards perched over 800 metres in the Val di Non.

“I practise mountain viticulture,” explains Biasi, who consults for many wineries, “so it’s something I strongly believe in, but as an adaptation strategy, I think it’s only a solution up to a point. It could work in Barolo, where they are considering extending the regulations to the north, or on Etna, where we could include the western slopes, or in Montalcino, where they could go beyond 600 metres. But what about those with wineries in Ferrara or Marsala? Should they sell all their vineyards and buy land in the Apennines? Move to Sweden? Let’s not forget that mountain viticulture is typically expensive and produces limited yields, so the resulting wines are priced at the high end. But if everyone makes €50 wines, who will buy them?”

New trends in taste and markets

“I also believe,” Biasi reiterates, “that another solution could be to change grape varieties and use those that perform better in the current climate. I’m about to say something quite heretical, but what if, in twenty years, we find that the Sangiovese grapes in Montalcino are overripe or half-dried by early August? In that case, who cares about Sangiovese? What matters is Brunello and preserving the territory: we’re talking about denominations of origin, not denominations of grape varieties. Let’s change the regulations, openly of course, to allow varieties that perform better in a given territory with the current climate, and everyone can decide which path to follow. After all, 70 or 80 years ago, there wasn’t much Sangiovese in Montalcino: it was mostly Moscato, and it worked very well until the climate changed. Then, when the time was right, people rightly turned to Sangiovese. In my view, we shouldn’t be too attached to grape varieties; a grape variety is just a tool, like a winemaker, a barrique, or cement or steel vats, like spur pruning or Guyot training systems, all of which are used to enhance a territory.”

Mountain viticulture certainly represents an innovative and bold response to the challenges posed by climate change, and the wines produced at high altitudes, with their freshness, complexity, and distinctive characteristics, currently seem to appeal to a large segment of consumers. But is this the path that must be followed to adapt Italian (and global) viticulture to the challenges ahead? Or will the focus be on preserving wine-growing areas by embracing resistant grape varieties? We’ll have to wait and see what ends up in our glasses.

Meloni: "Tariffs? If necessary, there will be consequences. Heavy impact on agri-food sector"

Meloni: "Tariffs? If necessary, there will be consequences. Heavy impact on agri-food sector" The Government honours the greats of Italian cuisine, from Bottura to Pepe. Massari: "Thank you, Meloni, the only one who listened to us"

The Government honours the greats of Italian cuisine, from Bottura to Pepe. Massari: "Thank you, Meloni, the only one who listened to us" "We must promote a cuisine that is not just for the few." Interview with Massimo Bottura

"We must promote a cuisine that is not just for the few." Interview with Massimo Bottura Wine was a drink of the people as early as the Early Bronze Age. A study disproves the ancient elitism of Bacchus’ nectar

Wine was a drink of the people as early as the Early Bronze Age. A study disproves the ancient elitism of Bacchus’ nectar "From 2nd April, US tariffs between 10% and 25% on wine as well." The announcement from the Wine Trade Alliance

"From 2nd April, US tariffs between 10% and 25% on wine as well." The announcement from the Wine Trade Alliance