by Attilio Scienza

Why is the use of amphorae making a comeback in many vineyards, not just in Europe? This was discussed at Amphora Revolution, an event born from the joint venture between Merano Wine Festival and Veronafiere, which just concluded in Verona (June 7-8). Let's start with the advantages. Clay can be thought of as a middle ground between steel and oak. Stainless steel allows for an oxygen-free environment and does not impart any flavor to the wine, though it can sometimes cause reduction phenomena. Oak barrels, on the other hand, allow oxygen to reach the wine, and the tannins from the wood can also influence the wine's aromas and flavors. Like oak, clay is porous, allowing slight oxygenation that gives the wine a deep and rich texture, but like steel, it is a neutral material that does not impart any additional flavor.

Characteristics of amphora-produced wines

Typically, the winemaking process in amphorae involves destemming the grapes but not crushing them, macerating the skins for up to six months, excluding the use of sulfur dioxide and selected yeasts, and controlling the temperature during fermentation. Wines produced in amphorae generally exhibit higher volatile acidity, a higher polyphenol content that determines a more intense color, more spicy and vegetal aromas with hints of aromatic herbs, and are more tannic and persistent on the palate. These wines are characterized by notable physical-chemical and microbiological stability, allowing for long bottle aging without oxidation issues.

Amphora in history

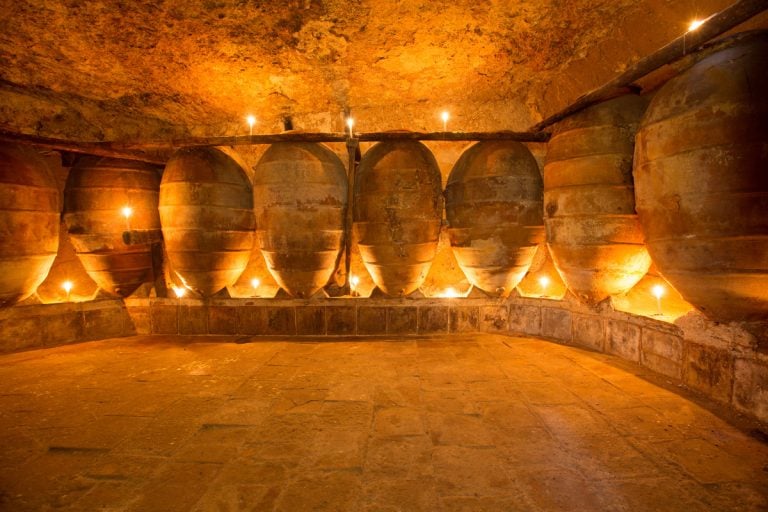

The production of orange wines, the Amber revolution, and winemaking in amphorae represent a true "return to the future," where clay and the shape of the amphora identify with the great mother, the Jungian archetype, of the earth, the underground world, and procreation, and in a strict sense, the womb. Historically, the amphora is a form of terracotta vessel used in antiquity for storing and transporting wine. The name derives from the Greek word amphoreus, "carried from both sides." Each Mediterranean region was characterized by amphorae of different capacities and shapes. Besides wine, amphorae were used to contain oil, honey, preserved fish, and large ones for cereals.

For fermentation, dolia were used instead, terracotta containers without handles, usually larger than amphorae, reaching heights of up to two meters in Roman times. Grapes were crushed and fermented in dolia with the skins removed only after the spring equinox. Wine aged in clay or amphorae has grown in popularity in recent years. But this technique is far from new. In fact, the practice originated in what is now modern-day Georgia, around 6,000 years ago.

The use of terracotta in Italy today

Currently, the use of dolia is widespread in Georgia, the Caucasus (kvevris), and to a lesser extent in Spain, in La Mancha. In Italy, the technique of fermentation in amphorae was introduced about ten years ago, with Georgian containers by Joško Gravner in Collio, producing about 25,000 bottles using this method, sold at a very high price, and imitated by the Sgaravatti company in Padua, the Pievalta company in Ancona province, and COS in southeastern Sicily. Other companies are experimenting on a small scale with various vinification trials in dolia. These are still niche wines.

Why Arillo in Terrabianca's organic approach is paying off

Why Arillo in Terrabianca's organic approach is paying off What do sommeliers drink at Christmas?

What do sommeliers drink at Christmas? The alpine hotel where you can enjoy outstanding mountain cuisine

The alpine hotel where you can enjoy outstanding mountain cuisine Io Saturnalia! How to celebrate the festive season like an Ancient Roman

Io Saturnalia! How to celebrate the festive season like an Ancient Roman