Straight to the Point: How Have Production, Styles, and the Market Changed in Champagne? Few words wasted from one of Champagne's most iconic producers.

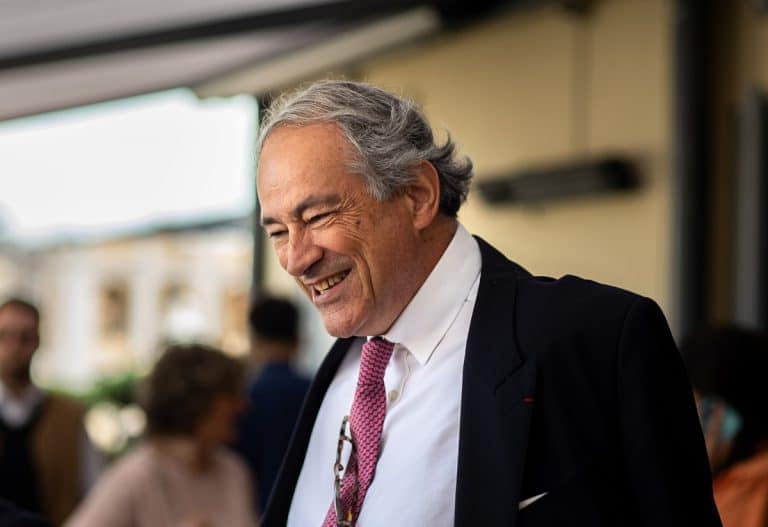

Bruno Paillard with his daughter Alice, who has been leading the Reims maison for some time. Photo by Studio Cabrelli.

Rapid-fire questions and answers, no beating around the bush… let's get straight to the heart of the matter. So…

How has Champagne (and champagne itself) changed over the past decades?

There are three main changes. The first is the climate: today, we harvest in August; fifty years ago, it was in October. My first harvest was in 1972, and it was a disaster. We started picking on 1 November. This has changed the aromatic profile of the grapes. Today, grapes ripen between 85 and 90 days after flowering, whereas historically, it was 100 days… And it’s not the same kind of ripening. Consequently, the structure of the wine has changed.

But you’ve had your own approach, your own style, from the beginning…

When I started, the market was 70% Brut and 30% Demi-sec. I began with only a Brut; I’ve never made a Demi-sec. If I want to drink a sweet wine, I’ll open a Sauternes or a Moscato di Pantelleria, which have natural sugars. For me, Champagne is about freshness, energy, tension. For twenty years now, we’ve been the only maison producing solely Extra Brut.

Paillard, father and daughter, in the vineyard. Photo by Studio Cabrelli.

Is it difficult to buy a vineyard in Champagne? Are there laws that make it quite complicated?

It’s true; there’s a political system that, in theory, aims to favour the small players. But only in theory because, if we look at it, the LVMH group owns 50% of the vineyards belonging to maisons. Theory is one thing, but practice is another. If I reach an agreement with a grower to purchase their vineyard, we go to the notary to draw up the contract. The notary drafts it, but before finalising the deal, they send the document to the SAFER (Société d’aménagement foncier et d’établissement rural), a rather politicised organisation controlled by the growers’ union. LVMH, curiously, buys vineyards very easily, probably negotiating with SAFER before the purchase. As a result, they are at the forefront of all significant transactions, owning vineyards in every cru of the region.

So, what’s your strategy? You’re in a sort of limbo, neither a large maison nor a récoltant.

LVMH produces 70 million bottles, while we produce 300,000 to 400,000 a year. We practically don’t exist. But we own vineyards: they cover 65% of our needs, most classified as Grand Cru, where competition to buy is very intense, which leaves us relatively secure for the future. What’s the other advantage? Being growers, we farm according to our standards. We’ve never used glyphosate and work the soil superficially to force the root system to delve deep into the “craie” (chalk) to extract the best it can offer.

According to a renowned oenologist, a third of Champagne wines are exceptional, a third are good, but the remaining…

Yes, it’s true. You should know that there are 4,000 récoltants, but only 1,000 produce their own Champagne. The other 3,000 sell their grapes to cooperatives, which vinify, produce the sparkling wine, and redistribute it to members who want to sell under their own label. So, not all Champagnes from small producers are “homemade.” Then there’s another trend today: the search for “parcellaire” Champagnes.

In some ways, it’s the antithesis of the traditional Champagne concept.

A great Champagne is a composition: the canvas of an artist. At Paillard, we have 60 plots; perhaps two or three could produce a parcellaire. For me, the important thing is to sign a style. When I see a Caravaggio, I recognise it—it’s either an original or at least from Caravaggio’s school. And it’s the same with Picasso.

Do you work differently from the big maisons?

We are more traditional in our techniques and management of reserve wines. We rotate our stock over five years, whereas they do so in two, and their base Champagnes end up resembling each other: hyper-oxidation of the musts followed by vinification in reduction—a quicker and more economical system. It’s “financial” oenology. For me, it’s not the true taste of Champagne. We are vineyards in the north, on chalky soils; we should feel this in the bottle!

“US Tariffs? The consequences will be devastating for Italian wine.” Cooperatives criticise Italian politics

“US Tariffs? The consequences will be devastating for Italian wine.” Cooperatives criticise Italian politics Don’t call It a rooftop: it’s a museum, a kitchen, and a stage

Don’t call It a rooftop: it’s a museum, a kitchen, and a stage The farmhouse with kitchen in the Mantuan countryside where you can eat (and produce) free-range pork

The farmhouse with kitchen in the Mantuan countryside where you can eat (and produce) free-range pork Six thousand wines and two thousand spirits. The story of three friends who opened their dream venue in Milan

Six thousand wines and two thousand spirits. The story of three friends who opened their dream venue in Milan In Val d’Orcia, a winery is ready to dazzle with haute cuisine. Here's the new opening aiming high

In Val d’Orcia, a winery is ready to dazzle with haute cuisine. Here's the new opening aiming high