In the United States, a new Caribbean cuisine is emerging. Chefs originally from the Antilles, tired of executing recipes reflecting a classical, if not Eurocentric, approach, decide to take the plunge to tell a different culinary story, more in line with their roots: an "American story with Caribbean influences." This confirms the cosmopolitan vocation and increasingly heterogeneous nature underlying the American gastronomic proposal.

Course Reversals

In recent years, the ranks of chefs "discovering" Caribbean culinary traditions have been growing. In particular, those of individual islands (including the "Italian" one of Aruba). As reported by The New York Times, many of these chefs, mostly first-generation Caribbean-Americans trained in classical cuisine, are starting to specialize in the specific preparations of each island and their evolution over time. Some, in search of their culinary identity, have abandoned the path in prestigious and sophisticated restaurants to explore the roots and heritage of their places of origin. Thus, after years of working in refined European establishments in cities like New York and Washington D.C., they have taken a different path but one consistent with their respective backgrounds. The testimony of Haitian-American chef Gregory Gourdet is emblematic: "I spent so much time learning and cooking other people's cultures that I wasn't learning and sharing my own." This sentiment resonates with the commitment to oneself, as expressed by compatriot Chris Viaud (referring to the involvement and curiosity of customers about the stories behind dishes like braised chicken in Creole sauce): "It really resonated with being true to myself." Paola Velez, a pastry chef and founder of Bakers Against Racism, found her stylistic signature only later when, at the restaurant Kith and Kin, she fully embraced her cultural heritage by adapting ingredients from the Dominican area to the technical bases of French cuisine, starting with the carrot cake with passion fruit glaze and plantain buns. Regarding professional course reversals, there are also those who felt the call of their homeland to the point of converting their restaurant into a cuisine focused exclusively on recipes from their place of origin. Exactly what Nelson German did: transforming his California establishment into a completely Dominican proposal.

The Cuisine of the Islands

"Cooking is a place where we can enlarge our island." These are the words of the chef from Trinidad and Tobago, known on the New Orleans dining scene as Queen Trini Lisa, and they resonate with the spirit of this new Caribbean movement eager to deepen and disseminate island recipes. In this direction, no one better than the Martinez brothers can represent the movement. With their Celeste in San Juan, opened since 2022, they work meticulously on local ingredients through a network of trusted producers, especially fishermen. Diners are thus "educated" about the island's wealth, amazed that yellowfin tuna (served by them) can also be caught near Puerto Rico.

The interpretation of culinary tradition is not rigid. These U.S.-made chefs, influenced by their family history developed on the shores of the Caribbean Sea, give a special touch to the dishes. Chef Tavel Bristol-Joseph, for example, gives a "local" reinterpretation to Guyanese pepperpot, regularly served at his Texas-based Canje restaurant. The stew, usually considered a unique dish prepared with fragrant broth and accompanied by cassareep (a typical juice made from cassava), is here made with wild boar meat; in this case, that of an invasive species roaming Texas.

Caribbean-American Community and Culture in the United States (and beyond)

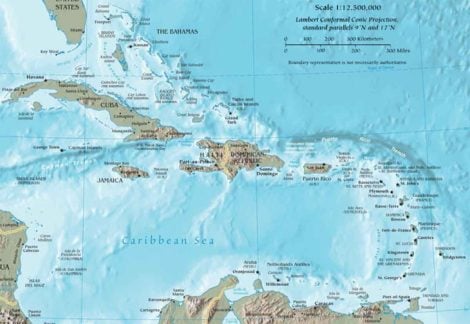

Caribbean-Americans constitute a minority in the country, but not a small one. According to data provided by the Migration Policy Institute, a think tank analyzing migration flows, 46% of black immigrants in the United States come from the Caribbean. They come from about 13 countries, from an area that stretches from the Bahamas to South America. In the U.S., a crucial role in spreading the tastes and customs of the islands has been played by Caribbean enclaves in New York and Miami (where the largest Cuban community in the country is now recorded), thanks in part to takeout comfort food (including Jamaican) prepared by immigrants from the 1970s.

In the "Anglo-Saxon" context, London's multi-ethnic soul stands out. The city, which saw a massive influx of labor from the Caribbean in the 1940s to cope with the post-war labor shortage, now hosts in one of its gentrified neighborhoods the largest Jamaican community in the world. It's no coincidence that the Brixton district is also known as Little Jamaica, with plantains and other fruits from the Antilles brightening the stalls of its characteristic market. Regarding catering, the appearance of fine dining with a Caribbean imprint in the United Kingdom is owed to a chef originally from Jamaica. Executive chef Collin Brown has long made loyalty to his indigenous roots a distinctive feature of his cuisine.

The Caribbean represents a collection of archipelagos expressing multiculturalism delivered by history. Influenced for centuries by indigenous populations, European colonialism (not just conquistadors), African slavery through the transatlantic trade, and finally by successive South American (as well as Asian) migrations.

Despite this cultural heterogeneity, the area is often considered by common thought as a monolith. Similarly, this bias also affects its culinary culture. Such a common perception consequently flattens Caribbean food. It is often identified simply as fruity or able to entice only tourists and is simplistically attributed to a macroscopic area that overlooks the differences between the various islands.

Despite this, given the push of the new Caribbean avant-garde in the kitchen, optimists abound: "Historically, the kitchens of people of color are not celebrated (in the same way) in the gastronomic world. But this thing is changing..."

Burgundy’s resilience: growth in fine French wines despite a challenging vintage

Burgundy’s resilience: growth in fine French wines despite a challenging vintage Wine promotion, vineyard uprooting, and support for dealcoholised wines: the European Commission's historic compromise on viticulture

Wine promotion, vineyard uprooting, and support for dealcoholised wines: the European Commission's historic compromise on viticulture A small Sicilian farmer with 40 cows wins silver at the World Cheese Awards

A small Sicilian farmer with 40 cows wins silver at the World Cheese Awards Women are the best sommeliers. Here are the scientific studies

Women are the best sommeliers. Here are the scientific studies Where to eat at a farm stay in Sicily: the best addresses in the Provinces of Trapani, Palermo, and Agrigento

Where to eat at a farm stay in Sicily: the best addresses in the Provinces of Trapani, Palermo, and Agrigento