by Claudio Ferlan

Food cultures in pre-industrial eras were deeply tied to natural cycles of light and darkness, warmth and cold. They adapted to the rhythms dictated by solstices and equinoxes. According to Christian tradition, it was during a crucial moment in these cycles—the wintersolstice — that Jesus of Nazareth was born in Bethlehem. Believers—and many skeptics—raised in Christian culture celebrate his arrival with generous feasts, preferably enjoyed in the company of family, along with a ritualized exchange of gifts. When Jesus made his earthly appearance, it was during the Pax Romana and the reign of Gaius Julius Caesar Octavian Augustus (27 BCE–14 CE).

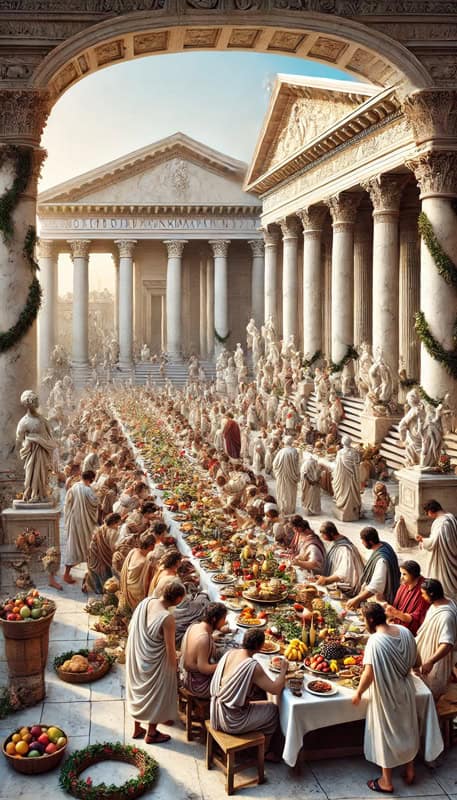

The Roman Saturnalia in late December

In Rome at the time, a highly significant festival was celebrated in late December: the Saturnalia, dedicated—unsurprisingly—to Saturn, the god of agriculture and prosperity. He symbolized a mythical era of abundance, equality, and peace. Initially lasting just one day (17 or 26 December, sources differ), Emperor Augustus extended it to three days, and later decades saw it grow to an entire week (17–23 December). What was being celebrated? The Sun, which, after a long decline, began its triumphant rise again. Invincible and undefeated (Sol Invictus), it was reborn at the solstice. The new Christian religion would reinterpret this event as the birth of Christ, the new Sun of salvation—invincible and resurrected like the celestial body.

Feasting After the Harvest

As the Sun waned, in pre-Christian Rome as in many other ancient cultures, the harvest was over—good or bad. Surviving the winter depended on reserves, including animals, not all of which were destined to survive the cold season. Some were sacrificed: hens past their prime egg-laying years (wisdom has it that older hens "make good broth"), castrated cockerels turned into capons, aged cows and oxen, and well-fattened pigs.

Preparing for the feast involved some dietary sacrifices to fully enjoy the eventual abundance. This is reflected in the complex calendars of fasting and abstinence of the Christian Middle Ages, which insisted that on December 25th, one should forgo nothing. Joyful celebration required paying homage even to a restrained appetite, provided it avoided the sin of gluttony.

During Advent, vegetables and fish, even the prized eel cooked and preserved in vinegar (especially large female capitone eels), took center stage. Meanwhile, the slaughter of pigs was—and remains—followed by the skilled work of butchers, who waste nothing from the animal, producing a wealth of delicacies. Some, such as cotechino (sausage wrapped in pigskin) or zampone (stuffed pig’s trotter), are meant for immediate consumption; others, for longer preservation.

Fresh fruit was scarce in winter, requiring reliance on stored or imported varieties, such as citrus fruits from southern regions, although dried fruits were the more common option for consumption and gifting.

Neapolitan artistic Nativity scene

The Christian gastronomic renewal

Under Christianity, many foods remained central to festive tables, though recipes evolved with the addition of new spices or the increasingly frequent appearance of pasta in broths. These adjustments catered to new palates and tastes.

Saturnalia rituals were not limited to feasting. They also included the suspension—or even reversal—of certain social norms, where masters served their slaves, along with games and the exchange of symbolic gifts such as candles or figurines. Homes and streets were adorned with greenery, garlands, and lights, creating an atmosphere of joy and tolerance.

Feasts and celebrations throughout human history

But it wasn’t only the Romans—or Christians—who celebrated the year’s shortest day, the lengthening of days, and the cycles of fertility and abundance. History abounds with such festivals, offering an adventurous journey through time and space.

In the American Southwest, on the plateaus of what is now northern Arizona, the Hopi—a Native American nation of Puebloan farmers—celebrated ceremonies deeply tied to the Sun’s cycles. Soyal, for instance, lasted sixteen days, almost as long as our Christmas school holidays. This festival marked the Sun’s return to the sky (more of an awakening than a resurrection) and brought hopes for a new season of growth and fertility.

Rituals of Renewal

Soyal included purification rituals to renew both the Sun and the faithful people, freeing them from the negative influences of the past year and preparing their spirits for the path ahead. Dances, songs, and sacred objects invoked nature’s spiritual forces to protect the community and ensure the return of the seasonal cycles—and the harvests they brought.

These spiritual forces, the kachina, received offerings of corn and descended to Earth during Soyal to visit the chosen people. Taking human forms, both male and female, the kachina were benevolent beings associated with natural phenomena like healing, rain, and plant growth. They left food and gifts for children and were celebrated with special food, such as piki, a thin bread made from blue corn flour (Hopi maize), mixed with juniper ash and cooked on hot stones.

The representation of the traditional Inti-Raymi of the ancient Incas, in Cusco, Peru

Under the Equator, where the Solstice falls in late June

For those living south of the equator, the winter solstice occurs in June. Among these cultures were the Inca of the Andes. For them, the Sun's journey resumed in late June, celebrated with the ancient Inti Raymi festival.

Inti, the Quechua word for the Sun, was a god who demanded and deserved invocations to ensure good harvests and blessings. This festival, like Soyal, was a time to express gratitude for the past year while welcoming the Sun’s revival, marked by the sacrifice of a white llama (a symbol of purity and fertility), ritual dances in special attire, and a procession through Cusco led by the Inca ruler.

Maize and more

Maize, a gift from Inti, was the central food of this banquet, appearing as chicha (fermented corn drink) in glasses and other dishes. Today, the festival still combines ancient homage with tourist attraction. One emblematic dish is chiriuchu, meaning "cold chili" in Quechua, prepared with ingredients sourced from across the country’s coast, highlands, and jungle.

The dependence of life on food

History need not force similarities, but neither should it ignore them. Feasts, dances, gifts, rebirths, celestial phenomena—these are markers of humanity's journey. At the winter solstice, people rediscover their shared destiny in dependence on the harvest and, ultimately, the food that sustains life.

God Bless those who don’t forego Stracciatella on the evening of December 25th. Here’s the recipe from a renowned Roman trattoria

God Bless those who don’t forego Stracciatella on the evening of December 25th. Here’s the recipe from a renowned Roman trattoria Hidden in an old district of Perugia lies one of Italy's cosiest wine bars

Hidden in an old district of Perugia lies one of Italy's cosiest wine bars George Washington had his secret recipe: here’s how Eggnog made a comeback in Europe

George Washington had his secret recipe: here’s how Eggnog made a comeback in Europe Historical breakthrough: Italy will also produce dealcoholised wines. Lollobrigida signs the decree

Historical breakthrough: Italy will also produce dealcoholised wines. Lollobrigida signs the decree If you say Syrah, you say Cortona. The story of Stefano Amerighi and other Tuscan producers

If you say Syrah, you say Cortona. The story of Stefano Amerighi and other Tuscan producers