In Le Calandre's spring menu, Massimiliano Alajmo presents a dish meant to be consumed in complete isolation, providing earplugs to each diner. This isn't the first time Massimiliano Alajmo has explored the role of sound at the dining table. Nor was he the first chef to do so: Henston Blumenthal's "The Sound of the Sea" about fifteen years ago accompanied a seafood dish with the sounds of seagulls, recreating the original environment of the ingredients and amplifying its impact on the eater. Meanwhile, Nino Di Costanzo, with the dessert "Napul’è," created an emotional panorama enhanced by Pino Daniele's song. Those were different times, and the challenge of synesthesia in those terms now seems somewhat naïve. Indeed, Alajmo's more recent "Vibrazioni – gioco al cioccolato 2018" went further, urging diners to listen to the sounds each one produced, amplified by hidden sensors under the dessert plate: 16 crunchy, crispy, soft, dense, and liquid preparations. A game, certainly, that encouraged slowing down and becoming aware of every gesture, bite, and sip, but also, and above all, an approach to the role of sound in food, still unexplored.

Inner sound: an exploratory possibility

Alajmo, on the other hand, sought the intersection of consistencies, sounds, and self-perception in food. He did this by adding elements of different structures to a meat bite, guiding the tasting moment to the point of making the diner unrecognizable to themselves while chewing. The next step was to investigate inner sound, eating in complete silence, in that amplified void created by earplugs. "We conducted tests: if one can isolate themselves, it's pleasant and regressive," explains the chef of Le Calandre, "and it's an almost hypnotic tasting that allows for a strong internal exploration." But it's not just about creating the conditions for distraction-free reflection, focusing all attention on what is being eaten; it's also about amplifying internal noises: "Hearing is a neglected sense in the kitchen, but what we hear when we eat and drink is more important than we think."

The crunchy

The work on sound overlapped with that on crunchiness in "Suono N'uovo," a pasta dish prepared with a starch gel and sanitized eggshell powder, reminiscent of yogurt with honey and shell that his grandmother used to prepare for him as a child. The tastings were not satisfactory: the crunchiness is an interesting sensation, but in this case, it gives an unpleasant sandy feeling. The same test, conducted with ears plugged, leads to a different path where the overall taste is no longer related to the goodness of the dish but refers to internal exploration. "It opened up a world for us," comments Alajmo. And it convinced them to delve even deeper, seeking the collaboration of doctors, psychologists, and other professionals not necessarily connected to gastronomy.

On the one hand, Alajmo delves into the reasons for the preference for crunchiness in our culture – for the role of chewing in digestion, because it is associated with the idea of freshness and wholesomeness of food, but also because it refers to a primitive legacy of biting as a vital impulse, and for its cognitive function of conquest, memory, imprinting, and learning. On the other hand, he investigates the role of sound in tasting, which is particularly evident in crunchy foods and can be perceived even before eating: just think of the noise a potato chip makes when it breaks.

The sound of food in tasting

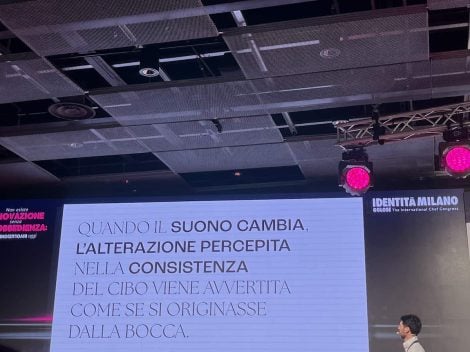

This is because sound delivers information about food that is unconsciously received and added to other information, conditioning the taste. It is an involuntary mechanism, proven by physicists Charles Spence and Nax Zampini in a 2008 experiment called "Sonic Potato": by amplifying the high-frequency sounds perceived when biting into Pringles, there was a perception of crunchier and fresher chips. Essentially, by increasing the noise, one thinks that the change is in the mouth, even when it is only an acoustic variation.

And this happens during tasting but to a different extent even before. "Have you ever wondered why potato chip bags are always noisy? Because that sound anticipates the noise of crispy chips, making them seem even crunchier." A similar sensation occurs, he explains, in sparkling wine: listening to the noise when it is uncorked and effervescent makes the bubbles feel more, while strident noises worsen the tasting experience. "If we eat not too crunchy breadsticks in a noisy environment, our brain processes the sound and reproduces to the brain the acoustic information given by the breadsticks, enhancing them to make them sound crunchy even if they are not." Moreover, each of us has a different soundbox; the same dentition offers a different experience to each one because the vehicle of sounds is not only external to humans but also internal, connected to the organ of hearing, the jawbones, and the skull's conformation. So everyone has a personal experience of the sound environment, and eating in a bubble of silence, as in the upcoming menu at Le Calandre, can greatly amplify the process of alignment with one's internal sounds. Not bad at all.

US tariffs: here are the Italian wines most at risk, from Pinot Grigio to Chianti Classico

US tariffs: here are the Italian wines most at risk, from Pinot Grigio to Chianti Classico "With U.S. tariffs, buffalo mozzarella will cost almost double. We're ruined." The outburst of an Italian chef in Miami

"With U.S. tariffs, buffalo mozzarella will cost almost double. We're ruined." The outburst of an Italian chef in Miami "With US tariffs, extremely high risk for Italian wine: strike deals with buyers immediately to absorb extra costs." UIV’s proposal

"With US tariffs, extremely high risk for Italian wine: strike deals with buyers immediately to absorb extra costs." UIV’s proposal Meloni: "Tariffs? If necessary, there will be consequences. Heavy impact on agri-food sector"

Meloni: "Tariffs? If necessary, there will be consequences. Heavy impact on agri-food sector" The Government honours the greats of Italian cuisine, from Bottura to Pepe. Massari: "Thank you, Meloni, the only one who listened to us"

The Government honours the greats of Italian cuisine, from Bottura to Pepe. Massari: "Thank you, Meloni, the only one who listened to us"