Easter in the UK

Along with Christmas, Easter is the main Christian holiday marking the start of spring and the end of the Lenten fast. For this very reason, most countries of Christian faith consecrate the holiday with tables laden with succulent meals, celebrating abundance and enjoyment of food after 40 days of austerity. There are nations, Italy in the lead, where recipes vary according to region, with a vast selection of savoury and sweet baked specialties. Other parts of the world, like the UK, where the typical Easter foods are more limited, but certainly not less interesting. As in all Christian, Catholic, Orthodox or Protestant countries, in Great Britain also is the time-honoured tradition of bestowing chocolate eggs to loved ones. This custom originates from the meaning of the Easter resurrection of Christ. The egg represents new life. Sugar, marzipan or chocolate, Easter eggs as we know them only go back to the last century.

Hot Cross Buns, history and legend

Eggs aside, each country has its own Easter specialty. The British, as we said, only have two, both dating back to the Middle Ages. The most common of the two, later exported to Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa is hot cross buns, a sweet roll flavoured with spices and studded with sultanas. On the top surface of the bun is a cross, in remembrance of the Holy Cross. According to legend, hot cross buns were born in St. Albans, in Hertfordshire, thanks to Thomas Rocliffe, a 14th century monk living in the St. Albans Abbey. From as early as 1361 this sweet – initially called Alban Bun – was handed to the poor on Good Friday. This custom however lasted only for a short time, because duringthe time of Elizabeth I of England, the London Clerk of Markets issued a decree forbidding the sale of hot cross buns. In this way the buns became a product made and eaten exclusively at home. The ban on selling hot cross buns purportedly lasted, according to legend, throughout the reign of James I of England (1603–1625). It wasn’t until 1733 that the sweets were again public domain. The Poor Robin Almanac, a satirical publication of the time, first shared the recipe: “Good Friday comes this month, the old woman runs. With one or two a penny hot cross buns”, supporting the idea that despite not being written about, hot cross buns were indeed well known at the time. Food historian Ivan Day states, “The buns were made in London during the 18th century. But when you start looking for records or recipes earlier than that, you hit nothing.”

Recipe: variations and eating habits

“There’s bread, like for Communion, spices, like the ones rubbed on the shroud that wrapped Christ’s body and laid to rest in the grave, and then the cross. They are bursting with Christian symbolism”. According to Steve Jenkins, Anglican Church speaker BBC News in 2010. Nowadays these small sweet buns can be found everywhere and made according to different recipes: variations on the traditional recipe include toffee, orange-cranberry and apple-cinnamon. Major supermarkets and small bakeries, pastry shops and restaurants bake them for Easter.In large distribution chains hot cross buns can be found year round, but they continue to be eaten only at Easter. Soft and spiced, hot cross buns are well loved mostly for their aromatic scent. The dough is in fact added with cinnamon, cloves. nutmeg, plus lemon zest and nuts, usually sultanas. They are commonly enjoyed for breakfast as is or smeared with jam or spreads, but the traditional way of eating hot cross buns is slicing them open, warmed in the oven and smeared with butter, Obviously paired to a steaming cup of English Breakfast tea.

Simnel Cake: the origins

Less known but equally tasty is Simnel Cake. A cake of fruit and marzipan originally prepared during the fourth Sunday of Lent. In this case also, there is no record of this holiday treat before the Middle Ages, when the first recipes started appearing. The meaning of the word "simnel" is unclear: there is a 1226 reference to "bread made into a simnel", which is understood to mean the finest white bread, from the Latin simila – "fine flour", but popular legend attributes the invention of the Simnel cake to Lambert Simnel. References howeverto the cake were recorded some 200 years before his birth. Different towns had their own recipes and shapes of the Simnel cake. Many produced large numbers to their own recipes, but it is the Shrewsbury in Shropshire, version that became most popular and well known.

Recipe: ingredients and symbolism

White flour, sugar, butter, eggs, sweet spices, nuts, lemon zest and candied fruit. These are the ingredients used in Simnel cake. Similar to the ones used for hot cross buns, and common in most Anglo Saxon sweets. Usually made with alternating layers of almond paste and layers of sponge, Simnel cake is covered with 11 marzipan balls representing the Apostles, excluding Judas. Sometimes the cake presents 12 balls but the twelfth represents Jesus, not Judas.

by Michela Becchi

Oenologist Riccardo Cotarella will also produce dealcoholised wine: "My first bottle will be out in October and it won’t be bad"

Oenologist Riccardo Cotarella will also produce dealcoholised wine: "My first bottle will be out in October and it won’t be bad" Dear natural wine world, enough with the constant polemics. If you don’t want to self-ghettoise, self-criticism is needed

Dear natural wine world, enough with the constant polemics. If you don’t want to self-ghettoise, self-criticism is needed In Bologna, there is an ancient osteria where you can bring your own food

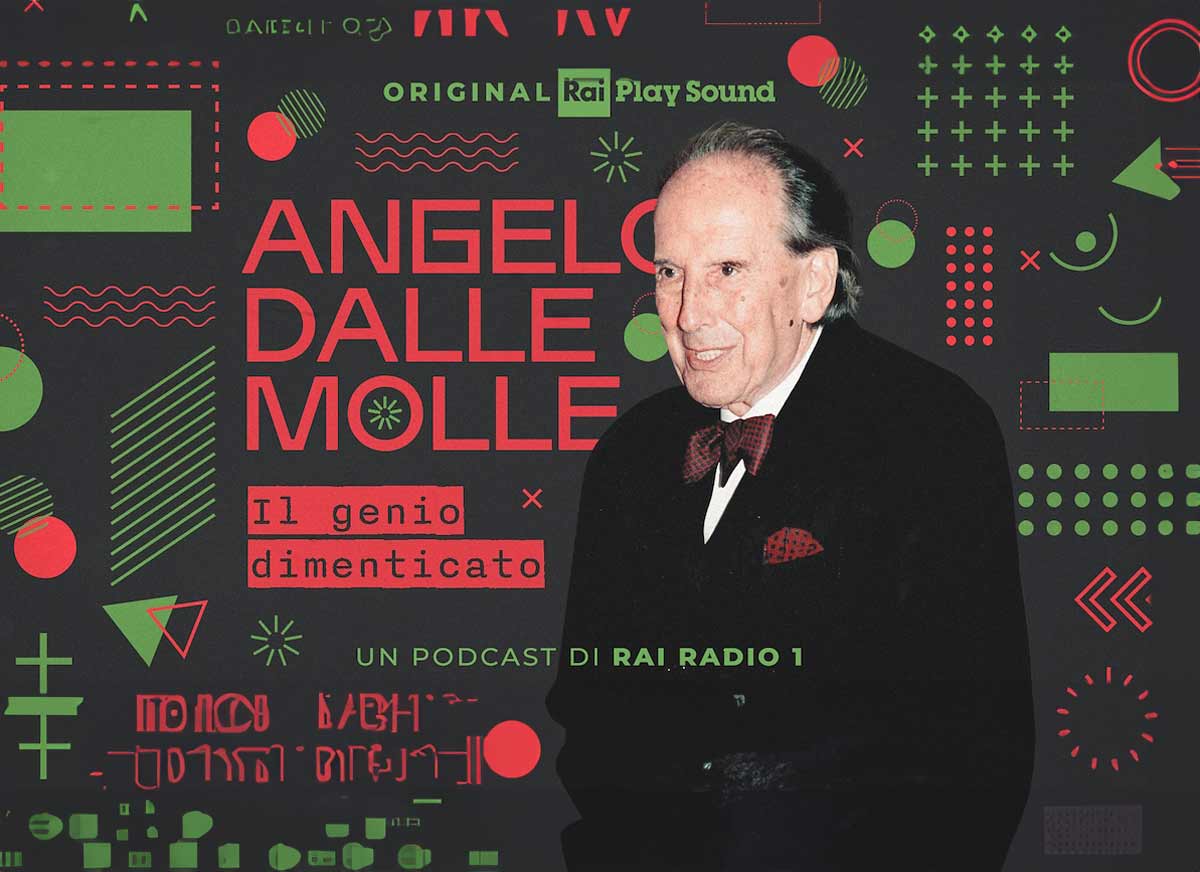

In Bologna, there is an ancient osteria where you can bring your own food Unknown genius: the Italian inventor of Cynar who was building electric cars and studying Artificial Intelligence 50 years ago

Unknown genius: the Italian inventor of Cynar who was building electric cars and studying Artificial Intelligence 50 years ago The 11 best-value Dolcetto wines from the Langhe

The 11 best-value Dolcetto wines from the Langhe