Parasite and the success of Korean culture

The success of South Korea's booth at the 2015 Milan Expo, thanks to its new gastronomic specialties, was only a foretaste of the interest in the culture of a country that would awaken a few years later. In this respect, the movie Parasite by Korean director Bong Joon-ho marked a milestone in 2019, winning first the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival and then the Best-Picture Oscar. In a five-year period, the Korean cuisine as well as the culture represented in the movie – particularly in the television series such as ‘Squid Game’ or ‘The Silent Sea’ – have overwhelmingly gained prominence on the global stage. And, in this regard, the movie has certainly played a key role.

The three families in Parasite

Food is not the main focus here, however it is represented in key moments, which see the intersecting lives of three families. Starting with the Kim family, who lives in a dark and suffocating semi-basement apartment, among alleys full of garbage and abject poverty: the father receives the unemployment benefit, the mother assembles cardboard boxes for a local pizza chain for a few won, the diligent son who wants to change his social position, and the teenage daughter with many dreams in her drawer. On the other hand, the Park family: a house in the upscale neighborhood, the housekeeper, the beautiful cars parked in the garage, a bored and quick-tempered wife, a listless daughter lost in her diaries, struggling with her first sexual experiences, a child victim of nightmares with a peculiar passion for painting, and not to mention the dogs, even more spoiled than the children. The third family is the Park's housekeeper Moon-gwang and her husband, who found shelter in the bunker beneath the house to hide from loan sharks who are after him. Here the housekeeper takes on a leading role (soon to be replaced by mother Kim): she will represent a major common thread among the families.

Food and social classes in Parasite

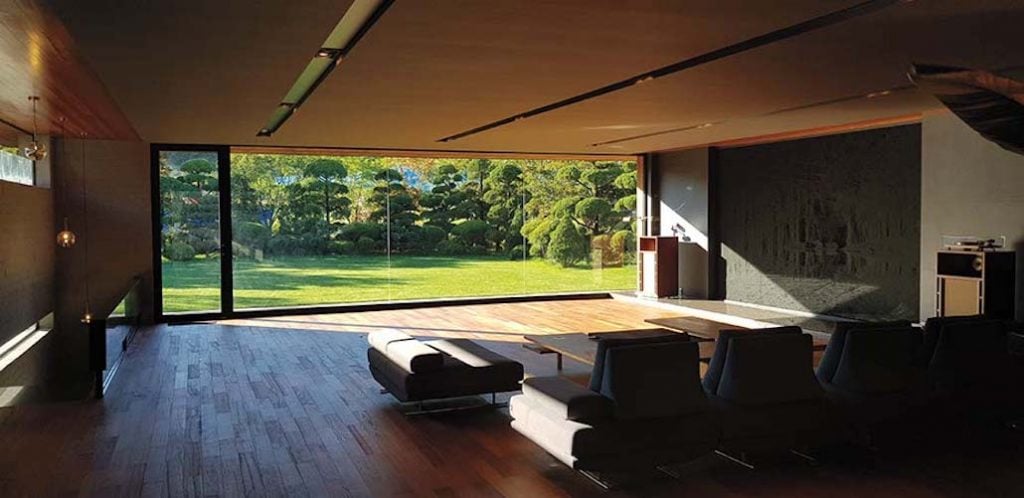

The contrast between poor and rich people, between those who are forced to live in the city slums and the wealthy class who enjoy their lives in minimalist villas surrounded by lush vegetation, is represented by food. A sharp contrast that is also chromatic – the gloom of the slums and the blinding light of the villa – but, first of all, culinary: the movie opens with the scene of a dinner in the Kim’s basement, a meager meal based on kimchi and soft drinks packaged in colored cans, made even more depressing by the stench coming from the street corners, which prevents the family from enjoying the little they have. When the father Ki-taek finally manages to enter the Park family's life by becoming their driver, and then by letting hire his wife as their new housekeeper, things begin to get better, starting at the table (Ki-taek can finally have a wholesome meal in a buffet restaurant). Thus, the family barbecue and the pork ribs are not just pure pleasure for the palate, but take on a much higher value that only those who have suffered hunger can attach to food. Even better if accompanied by soju, the distillate from rice and potatoes sold in green bottles. Unforgettable is the scene of the Kim in the villa binge eating and binge drinking Hite beers, Makgeolli, the traditional rice wine and whiskies: the owners are not home, and the family – to the tune of Gianni Morandi's ‘In ginocchio da te’ – voraciously consumes those luxury goods that were inaccessible to them until then.

The garden party and the master-servant relationship

Opening the third part of the movie is once again food, specifically the preparation of Ram-don. Due to bad weather, the Park family decides to return from camping well in advance and asks the housekeeper to prepare instant noodles – in particular Chapagetti and Neoguri that are also available in international stores in Italy – and sirloin, or beef cubes. The housekeeper will, however, enjoy her favorite dish alone at the table, while the first homicidal instincts of the other protagonists are starting to emerge. The garden party the next day to celebrate little Park's birthday, with waiters and chefs cooking pasta, salmon and gratin, completely destroys that codified model of social life. Here food represents the master-servant relationship (just as in the Hegelian dialectic so dear to literature and cinema), but above all an instrument of revenge and social redemption: it is no coincidence that the director, in an interview to Corriere della Sera in December 2020, stated that "before being a sociological category, capitalism is something tangible: our lives".

The finale: loss, food and death

A comedy that turns into tragedy, with a final murder committed with a kitchen knife and a meat and vegetable spit, a complex story in which food dictates the timing and beats the rhythm. We are at the end: Kim' s young daughter is killed by the former housekeeper’s husband Moon-gwang, who has finally escaped from the basement where he had been feeding on canned tuna, in front of a shocked Ki-taek and the indifference of the Park family, who are only concerned about their unconscious son. In a fit of rage, Ki-taek stabs Mr. Park, and that keeps triggering the general confusion at the party. A party that was supposed to be a moment of conviviality, organized down to the smallest detail, starting with the selection of prawns, meats and wines at the supermarket, turned into a collective sacrifice. Here the relationship between Love and Death of the Greek tragedy ca be replaced by the oxymoron Food and Death with the loss of family members. Salvation is just for the few.

by Marco Leporati

"Biodynamic preparations ave no effect on viticulture": The shocking conclusions of a Swiss study

"Biodynamic preparations ave no effect on viticulture": The shocking conclusions of a Swiss study Ten last-Minute Christmas gift ideas for a wine nerd

Ten last-Minute Christmas gift ideas for a wine nerd Food and wine tourism generates €40 Billion in revenue: Tuscany, Emilia-Romagna, and Puglia take the podium

Food and wine tourism generates €40 Billion in revenue: Tuscany, Emilia-Romagna, and Puglia take the podium "Non-alcoholic wine shouldn’t be demonised: it’s in everyone’s interest that it’s not just a passing trend". Piero Antinori opens the door to the category

"Non-alcoholic wine shouldn’t be demonised: it’s in everyone’s interest that it’s not just a passing trend". Piero Antinori opens the door to the category The Slovenian chef passionate about foraging who cooks in a remote castle

The Slovenian chef passionate about foraging who cooks in a remote castle