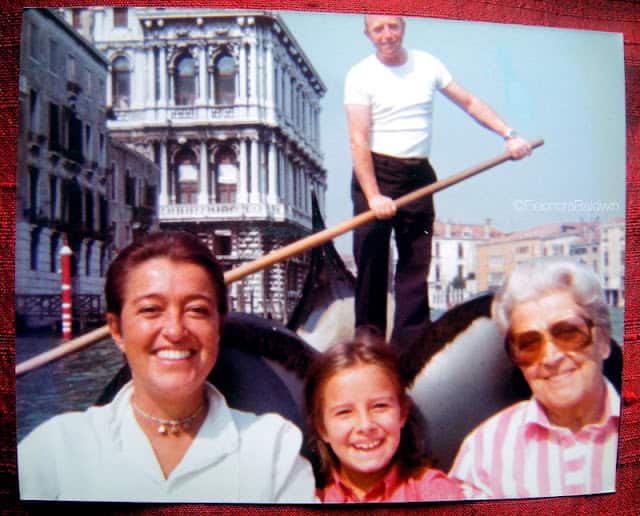

Our grandmothers, custodians of gastronomic secrets, family stories, and occasional mistakes, were vital guides for our sensory "weaning," an aspect that goes far beyond merely preparing a meal. With a single mother busy keeping things afloat, my grandmother was a fundamental figure. She practically raised me in the kitchen.

Cooking with Grandma

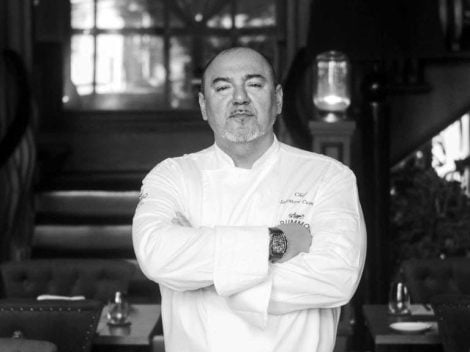

Watching her cook was not just an opportunity to learn techniques and recipes but a real rite of passage that made me understand how unique our bond was and how special the dynamics in the kitchen were. Her hands, which mine resemble more and more each year, taught me patience, attention to detail, and respect for genuine products. But Nonna Titta (Grandma Titta), known to the world as Giuditta Rissone, was not the typical granny.

Who my grandmother was, Giuditta Rissone

She told stories, baked cakes, and occasionally knitted, but in her youth, she was a renowned theatre actress with a childhood worthy of a novel. Born in 1895 into a family of theatre performers, she started touring the world with Ermete Zacconi's company alongside her parents and siblings from infancy, and she was on stage as soon as she could stand alone, forced to play only male roles (a girl in theatre was not good news). Grandma was the second youngest of four brothers: two played the younger roles, the less talented ones did manual labor; her father, my great-grandfather, was the prop master, responsible for painting backdrops, gathering furniture, setting up scenery, props, etc. His wife, my great-grandmother Luigia, was a seamstress and designed all the costumes for each production, in charge of cutting, sewing, and making costumes for the entire company.

This assortment of talents left Italy every summer, headed to South America, where the company performed mainly for Italian emigrants in theatres in Paraguay, Uruguay, Argentina, and Chile. Italians did not only land on Ellis Island. Grandma Titta did not speak a word of English, but thanks to these annual tours lasting months, she spoke Spanish fluently and had learned the basics of Portuguese. Once the season abroad ended, the company packed up the equipment and set-up and sailed the Atlantic on steamships to return home just in time for winter in the northern hemisphere (for the Italian theatre season). Titta loved the heat and summer because, for so many years of touring, summer had not been an option for her.

Later, as a teenager and then a young leading actress, her talent and charm brought her success. She soon became the star of many popular plays of the 1920s, her repertoire ranging from Greek classics to Shakespearean dramas to contemporary humorous, intelligent, and ironic pieces. In 1930 she met my grandfather, Vittorio De Sica, with whom she formed a company and later married seven years later. My mother was born the following year, giving Grandma Titta the opportunity to finally retire from the stage at the age of 42. Becoming a grandmother almost thirty years later, her glorious past somehow colored our interactions, our games, and our small habits at the table and in the kitchen, her great passion.

Despite the separation from my grandfather (divorce did not exist in Italy at the time), the difficulties Italy faced during World War II, her humanitarian commitment (she hid a Jewish family in the basement until June 1944), and being a single parent in the 1950s, Grandma managed to hold on and, much to her regret, act in 25 films since 1933. One of her last performances was in 1962, playing Marcello Mastroianni's mother in Fellini's masterpiece "8 1/2".

Grandma Titta's culinary gifts

Grandma Titta was a fun, unconventional, tender, and witty playmate. We played wonderful role-playing games, chatted, and gossiped like ladies having tea (made of sweetened tap water), and Grandma spoiled me as only grandparents know and are allowed to do. She taught me to appreciate good food thanks to her virtuous culinary skills. Within this important journey of knowledge and transmission of skills, I fondly remember some "sensory milestones" left to me by this extraordinary woman. Here are some of the most vivid in my memory.

Sherry and Parmesan (don't tell Mum)

Cooking together was a fun game, a form of life and taste education that is priceless. But Grandma Titta and I also had our little secret rituals in the kitchen and at the table. For example, while the dishes simmered on the fire, setting the table in the dining room, Grandma and I often treated ourselves to a very special aperitif. With a small knife, she taught me to slice the tip of Parmigiano Reggiano, and then poured precious drops of sherry into two tiny crystal glasses. We religiously savored this perfect combination. She explained how the saltiness and grit of the cheese "dance the waltz" with the sweet notes of dates, dried figs, and chocolate of the sherry. The graininess of the Parmesan chases each sip, which in turn leaves the mouth velvety and syrupy. It was an intimate moment that somehow shaped my taste buds. It was madness considering I was only seven years old. "Let's not tell Mum, if she finds out I'm letting you drink, she'll kill me."

The secrets of 'Bagnetto Verde'

Grandma Titta's green sauce, which she, being from Asti, called bagnèt vert, is the keystone of the complex ceremony of bollito misto, a cornerstone of the most important lunches. As a child, I watched her prepare this recipe hundreds of times. Always with the same crank parsley chopper, the good oil poured in a thread, the anchovies I had to clean of invisible bones, the dry bread soaked in vinegar, the capers in brine, and the hard-boiled egg yolk trick. At our house, bagnetto verde is still made exclusively this way.

Rolling out dough with a rolling pin

One Sunday, considering me capable (or worthy), Grandma gave me her precious one-meter-long rolling pin like a scepter. It was time to learn how to roll out dough. No Imperia machine, she did everything by hand. Flourishing the pastry board, she made me touch the wooden surface, its rough grain. Once the yellow dough was born, she explained how to exert minimal pressure at first and gradually increase the force as the dough thinned, and showed me how to tell if the dough needed more flour. When the surface began to expand, we laughed thinking of the "short blanket": stretching vertically the long and narrow strip had to be compensated with horizontal movements, and the shape instantly elongated into an opposite oval. Above all, she encouraged me to keep going, never to give up, and to test the limits of the dough's thinness depending on its use and format (agnolotti, tagliatelle, etc.). The rolling pin and wooden pastry board are still in their place, used less and less since Grandma and Mum are no longer here. Neither my sister nor I dare touch them out of respect.

How to make 'Bagna Cauda'

As a child, I feared the abundant amount of garlic in the bagna cauda Grandma made in winter, so she taught me her trick: halve the amount of oil and compensate with a cup of whole milk, to be poured into the earthenware pot. The same amount of garlic and identical procedure: the milk tames the strength of the garlic. It works, guaranteed.

Pasta with meat extract

Even today, when I feel the weight of deadlines and everyday life problems, I find comfort in the kitchen, just as Grandma and Mum did. While cooking with a whirlwind of worries in my head, I often automatically recreate Grandma Titta's recipes and involuntarily replicate those daily gestures of love I grew up with. To feel particularly close to her and everything she meant to me, I just need to open a jar of meat extract and put a pot of water on to boil. The combination of aromas and textures triggers a powerful Kafkaesque moment. Suddenly, I am transported back in time, to the house where I grew up, standing on a chair next to the kitchen counter, wearing my apron and watching Grandma dissolve spoonfuls of dark, tar-like beef extract in a small amount of pasta cooking water, along with some butter. We are preparing her pasta with meat extract, my "madeleine".

The aroma reaches my nostrils and I close my eyes. I hear the jingle of the 1970s news coming from the old cathode ray tube Grundig TV in the other room. Grandma's smile and her sparkling emerald eyes streaked with gold appear like a flash of a photograph. I find myself back in the present, looking down at the bowl in front of me. I notice the age spots on the skin of my hands are just like Grandma's. Her ring, which I wear on my right hand, gleams in the midday light in my small kitchen. I toss the drained pasta with the mixture of butter and extract and sprinkle a hint of grated Parmigiano Reggiano on top. The result is an unattractive plate of gray-beige pasta. With each forkful and bite, I am embraced by the tender and fleeting memory of her. I was ten years old when she died, leaving a hole in my childhood filled only with many memories and a unique imprint that shaped my nature and individuality. Thank you, Grandma, for making me understand that food is never just food.

The great Bordeaux exodus of Chinese entrepreneurs: around fifty Châteaux up for sale

The great Bordeaux exodus of Chinese entrepreneurs: around fifty Châteaux up for sale Dubai speaks Italian: a journey through the Emirate's best Italian restaurants

Dubai speaks Italian: a journey through the Emirate's best Italian restaurants In France, over a thousand winegrowers have decided to abandon wine production

In France, over a thousand winegrowers have decided to abandon wine production In Miami, a Restaurant Hired a Pair of Grandparents to Hand-Make Tortellini: The Story of Torno Subito

In Miami, a Restaurant Hired a Pair of Grandparents to Hand-Make Tortellini: The Story of Torno Subito Wine Spectator’s Tuscan focus: All the Italian labels featured in the Top 100

Wine Spectator’s Tuscan focus: All the Italian labels featured in the Top 100