Superstition runs deep in the Italian upbringing. Southern Italians are known to be more superstitious, although many unfounded beliefs, old wives tales and myths originate in all parts of the boot-shaped peninsula. Everyday good luck signs keep the average superstitious Italian’s tempo and may include anything from seeing a spider at night (this is a sure sign of monetary income), to finding a button on the ground (which signifies a new friendship is on the horizon). Did you know dropping things means someone is thinking of you? Or that when your nose itches, it's either “pugni o baci", punches or kisses? When you dream of someone dying, no worries: you've just added ten years to their life.

Rituals against the evil eye and other bad luck

There are several ways in which a superstitious Italian will act to on the other hand reject bad omens or what can be interpreted as bad luck. The crotch-grab is definitely one of these. Italian men will instinctively go there when faced with potential ill fortune, or say, cross paths with a nun, a black cat or an empty hearse. Nuances can go from a discreet brush, to a less-than-subtle squeeze. Another failsafe system (one that’s more PC at least) is always carrying a corno portafortuna. This is a red (or silver, gold, coral or plastic) bull's horn-shaped talisman known to scientifically deflect bad vibes. To parry the appearance of something negative or associated with ill fate, another common solution is gesturing the horns. Index and middle finger raised and hand pointed downwards. Note: while pointing upwards at rock concerts, in everyday life (especially in traffic) signifies calling someone a cuckold, a terrible offence!

The majority of Italian superstition occurs at the table

Oddly much of what Italians are superstitious about happens at the table, and has somehow to do with food. For example, single men and women should not sit at the corner of the dinner table, for they will never marry. Why is this? A reason might be that if seated at the corner of the table, the person is less visible and may go unnoticed, therefore will have "less chance" of finding a companion for the years to come.

Women on their menstrual cycle should definitely refrain from canning tomatoes, nor whisking together homemade mayonnaise: the results would be disastrous (for the sauce).

Crossing silverware on the table brings strife. This is a clear reference to crossing blades in a duel or a swordfight.

Two guests at the table who pass each other the salt shaker hand to hand (without putting it down on the table first) will get into an imminent fight with one another.

When eating a meal, one should never place a loaf of bread upside down on the table. The reason for this is a rather complex historical one. In the Middle Ages and all through the 1700s – an era grieved by daily decapitations and the Black Plague – a collective fear of death had made it strictly forbidden to touch anything that had been associated with death. This for obvious hygienic and sanitary protection, but there were more romantic reasons as well. The executioner or hangman was a terrible profession, one which involved living a very isolated life from the rest of the community, always avoiding contact with anyone else. Objects and foods intended for the executioner were also treated similarly so as to not come in contact with other people's belongings. The clothes of the hangman were washed in a separate area, and the food was cooked separately. As far as bread, bakers invented an easy way to separate and identify the bread intended for executioner, so that even in the oven, that loaf would not come near the bread intended for other citizens. This system was to turn the bread upside down and since then called it the "bread of the executioner". The aura of that ages-old macabre practice remains to this day when placing upturned bread loaves on the table.

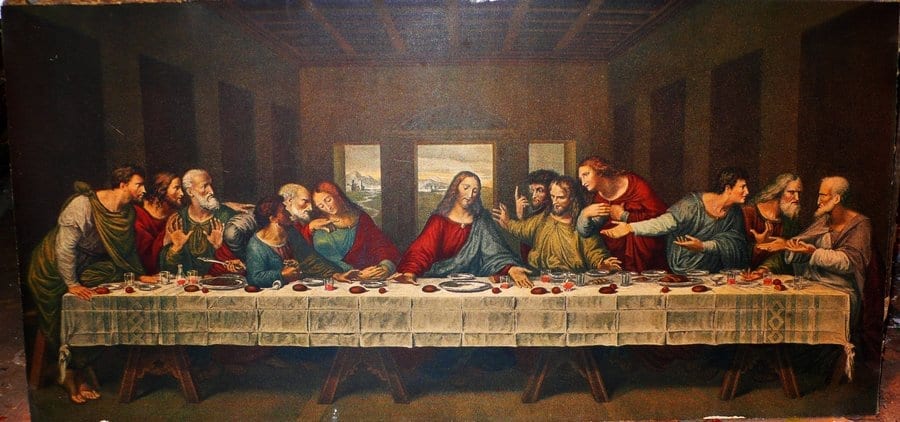

Seating 13 people at the table is considered the mother of all superstitions. At the Last Supper, Jesus sat with his 12 apostles before one of them, Judas Iscariot, betrayed him leading to his crucifixion.

Spilling food is not merely a waste

If Italians spill wine at the dinner table, they will wet their fingers in the fresh stain and dab some behind every person's ear. This will chase away the sin of wasted wine (very bad luck).

Tossing leftover bread crusts and crumbs in the trash? Italians always kiss them before chucking. Breaking bread at the table has been associated with the Host of Holy Communion for millennia. Throwing away food, let alone the body of Christ, has always been considered a sin, Catholic or not. The kiss is an apology.

Spilling olive oil and salt is also considered bad luck. This idea may have begun as a way to motivate folks to handle the expensive goods with more care. Ill fate associated with spilling salt comes as no surprise, considering how valuable salt was historically. Salt extraction was costly and labor intensive. It was furthermore used as a currency for paying Roman soldiers – hence the use of the word “salary” which derives from the word “salt”. There is however another more sinister angle on the salt superstition. Ancient civilizations were sometimes known to salt the earth of conquered lands, making the soil sterile as a sort of punishment. Spilled salt can be pinched and tossed over the shoulder. For spilled olive oil, on the other hand, there is no solution but mourning.

Wine and toasting

The ritual of wine drinking and toasting is another table-side topic which raises huge superstition controversy. For example, crossing glasses when toasting in a group is considered bad luck. Each drinker waits for their turn to clink glasses with the person opposite.

Another ill-fated practice is toasting with a glass of water. Non-drinkers and children allow a droplet of wine to stain their water, or simply choose another beverage for the toast. The reason for this can be attributed to a New World superstition: the US Navy urged officers not to toast with water aboard ships because it was thought to bring misfortune at sea, maintaining the thought that “water returns to water”.

It’s also bad luck to toast drinking from plastic cups. Non-glass receptacles can still be used to toast but best if done by touching knuckles instead of making contact plastic-to-plastic.

Pouring wine backhanded is a luck no-no. In ancient times rings with large stones easily concealed a snap-compartment that could contain poison. A flick of the wrist while pouring wine backhanded in a goblet could allow dispensing the hidden poison in an enemy’s drink.

Another very important rule when toasting is to always look into the other person's eyes. This too could be associated with fending off ill-intentioned drinking buddies.

Also, forgetting to take a sip after a toast, before setting the drink down, will bring seven years of bad sex.

The rules of Italian New Year’s eve

Celebrating New Year’s eve in Italy is more about superstition than ringing in the new calendar. There are precepts for the feast enjoyed at the table on the night of the 31st of December that no Italian completely overlooks.

Wearing red underwear, for example. Fire-engine red undergarments in close proximity to the private parts, is said to bring money and lots of intercourse in the coming year.

Another fortune-bearing midnight exercise is that of eating three white grapes by the twelfth bell ring (our Spanish cousins eat twelve, one for each bell toll). However, the most powerful luck-attracting measure on New Year’s eve in Italy is the menu. The typical capodanno ("head of the year") dinner is one monumental good luck attracting amulet. Eating stewed lentils and thick slices of cotechino generates positive vibes for the year to come. Best if eaten at midnight and not earlier to avoid jinxing their effect, lentils are said to bring money, while cotechino – a large spiced pork meat sausage made from pork rind and meat from the cheek, neck and shoulder, and usually seasoned with nutmeg, cloves, salt and pepper with a delicately flavored soft, almost creamy texture – represents phallic abundance.

If that’s not enough to make Italian table-side superstition contagious to even the most cynical sceptic, what will?

by Eleonora Baldwin

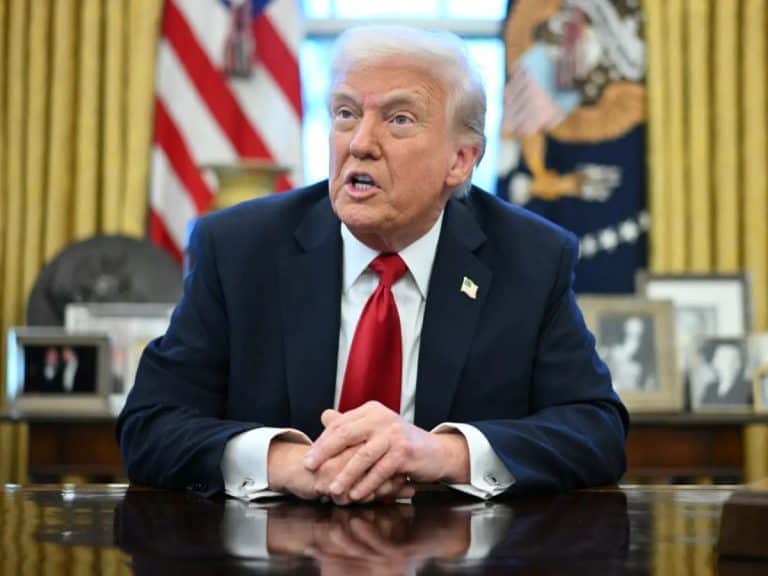

Farewell cacio e pepe in New York. "With tariffs, Pecorino Romano will also become more expensive." The warning from Giuseppe Di Martino

Farewell cacio e pepe in New York. "With tariffs, Pecorino Romano will also become more expensive." The warning from Giuseppe Di Martino Against tariffs? Here are the US foods that could be "hit"

Against tariffs? Here are the US foods that could be "hit" US tariffs: here are the Italian wines most at risk, from Pinot Grigio to Chianti Classico

US tariffs: here are the Italian wines most at risk, from Pinot Grigio to Chianti Classico "With U.S. tariffs, buffalo mozzarella will cost almost double. We're ruined." The outburst of an Italian chef in Miami

"With U.S. tariffs, buffalo mozzarella will cost almost double. We're ruined." The outburst of an Italian chef in Miami "With US tariffs, extremely high risk for Italian wine: strike deals with buyers immediately to absorb extra costs." UIV’s proposal

"With US tariffs, extremely high risk for Italian wine: strike deals with buyers immediately to absorb extra costs." UIV’s proposal