On 18th January 1964, Il Corriere della Sera headlined: "Italy is made: its cuisine is not. We are just beginning to unite (at the table) with spaghetti and panettone: for this, there are still no national studies or treatises." Exactly sixty years later, we are still asking what Italian cuisine is (and if it exists): but, just like then, panettone remains an undisputed national glory.

There are various legends about its origin: from Messer Ulivo degli Atellani, a simple baker’s apprentice who supposedly invented it out of love for the beautiful daughter of a baker; or from the legendary Toni, a servant of Ludovico il Moro, who presented it at the table as a replacement for a burnt dessert and had the fortune of baptising it as "Pan de Toni". Obviously, these are fanciful reconstructions that place the invention of panettone in a time when nothing comparable to today’s version existed.

The "Pan de Toni" interpreted by the Ottagono pastry shop of Mascalucia (CT)

The Christmas bread

The real story is much more recent and tells us not of the fortuitous insight of a pastry chef but of a slow technical evolution based on French and Austrian recipes. But let’s start from the beginning, when panettone didn’t yet exist (but meanwhile, here’s the Gambero’s ranking of the best artisan panettoni for Christmas 2024).

The ancient tradition of baking large sweet loaves for Christmas is widespread in many European countries. There were several types, variously enriched, simple preparations passed down orally, many of which have been lost over the centuries. One of the oldest Italian recipes is reported by the Bolognese agronomist Vincenzo Tanara in his L’economia del cittadino in villa (1644): "Our farmers... knead flour with yeast, salt, & water, or honeyed water, incorporating dried grapes and candied pumpkin with apples (candied with honey), adding pepper, and they make a large loaf, which they call Pan da Natale."

These sweet breads were characterised by their large size and were also called “panoni” or “panatoni”, and we can consider them the rustic ancestors of modern panettone.

At the time, there were already some types of more delicate, softer leavened breads, kneaded with flour, eggs, butter, and sugar, such as the "Pani de latte e zuccaro" described by Cristoforo Messisbugo in the mid-16th century. Some Christmas breads may have already had a more refined shape. Unfortunately, historical documentation on this is scarce, so these are merely assumptions.

The French brioche

In the following two centuries, pastry techniques made a huge leap forward, thanks to the French, who went on to create true gastronomic masterpieces. One of these is a particularly soft and light dough made with yeast and long fermentation: brioche. This speciality spread across Europe and is still the basis of various Italian specialities: from maritozzo to babà, and even brioches with tuppo.

By the mid-1700s, the path was already set, and La Cuisinière bourgeoise by Menon included a recipe for a "gateau de brioche" that could even be quite large, slightly smaller than a modern panettone, as seen in some paintings of the time. The French technique spread particularly in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, where it gained some success. It is difficult to say how much the Duchy of Milan, at the time under Austrian rule, was influenced by these sweet trends, but in the final years of the 18th century, we find one of the first mentions of panettone in the city of Milan: "The Milanese apothecaries and bakers at Christmas, to gift their shop visitors, make a very large bread called panatone. This bread is made with about one pound of flour, a quarter of butter, a quarter of sugar, a little bit of currants (raisins), and some other ingredients chosen by the baker." Milanese panettone was born: a rich and delicious dessert to enjoy during the Christmas holidays.

The Milanese panettone

Throughout the 19th century, references to the Milanese specialty multiplied, and it gained increasing notoriety. By the middle of the century, its success was such that it was being shipped across Europe and even participated in the 1864 national exhibition and the 1867 Paris exhibition. At the time, panettone was still a completely artisanal product, and the most renowned baker for making it was Milanese Paolo Biffi, who faced competition from Carlo Lorioli of Brera, Caffè Sanquirico, and Ambrogio Lazzaroni. The Biffi pastry shop is also remembered by contemporaries for making monumental panettoni "15 to 25 kilograms each, perfectly baked, which amazed the main cities of Europe", as reported in L’Imperatore dei Cuochi. Manuale completo di Cucina Casalinga e di Alta Cucina by Count Vitaliano Bossi, supported by head chef Ercole Salvi, published by Edoardo Perino in 57 issues in 1894-1895.

Ciambellone or panettone?

But what was the 19th-century panettone like? Descriptions are rare and not very detailed: we know it resembled the "ciambellone di Siena" – quite renowned at the time – but compared to that, its dough was "with candied fruits, but more airy, drier, so it could be preserved and kept intact even during long journeys". It wasn’t "very different from other similar preparations from Turin, Venice, Brescia, Pisa, and almost all other cities in Italy, which reproduced it under different forms and names."

Thus, it was denser and more compact than the modern version, sharing many traits with other local specialties, but it was becoming a celebrity beyond the Milanese borders.

The first recipes

There are not many cookbooks that include the recipe for the Milanese panettone, probably considered too complex for home cooking. The first description is in the Codice gastrologico economico of 1841 under the name "Cuvuluf, ossia panotto alla Milanese". This odd name hints at the Central European origins of the preparation, referring to the kugelhupf (now also known as gugelhupf or kugelhopf), a typical leavened pastry found in Alsace, southern Germany, Switzerland, Austria, and the Trieste-Gorizia area, where it is currently called Cuguluf.

The wheat flour, probably not very "strong" and therefore unable to support long fermentations, was supposed to result in a large doughnut with a fine crumb structure.

In the 1960s, there was a need to lighten the dough and raise the panettone’s dome by using a higher quantity of gluten. Lacking access to strong wheat flours, semolina was chosen as a solution, which allowed for longer fermentations, resulting in a more airy structure, but the results were still far from today’s techniques.

Angelo Motta’s panettone

The Milanese panettone, growing bigger and richer, was becoming a real technical challenge for bakers. While the French remained faithful to their brioches, perfecting the process thanks to masters like Antonin Carême and his successors, Italy was refining techniques to create ever more impressive leavened goods.

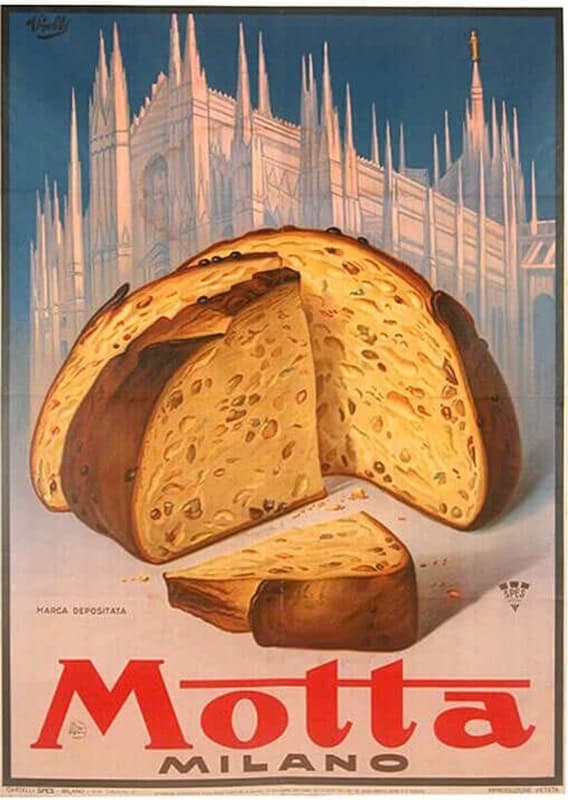

In this context, in 1919, Angelo Motta opened his pastry laboratory in via Chiusa in Milan. Starting with limited resources and few tools, in less than ten years he stood out for the quality of his panettoni. By investing in modern machinery, he increased production, and by the mid-1930s, his "Dolciaria milanese" was already among the leading companies in the sector, distinguishing itself from the artisanal bakeries of Milan. By the end of World War II, Motta was the second largest Italian confectionery company, with panettone as its flagship product.

The first industrial panettoni

But what were the first industrial panettoni like? They were taking on the appearance we know today, thanks in part to the use of stronger wheat flours, such as "Hungarian flour", which had been on the market for some time. However, they contained less butter and fewer ingredients, making them less indulgent for our current taste. The typical cylindrical shape with a swollen top was only introduced after the mid-1930s with the use of paper molds; before then, panettoni had a lower domed shape, similar to the traditional Christmas bread.

A universal success

Panettone had now reached its industrial dimension, which allowed for the production of large quantities to meet demand both in Italy and abroad. Meanwhile, many compatriots had emigrated overseas, where they continued to keep Italian culinary traditions alive. Recipes for festive foods were a shared heritage and were constantly re-proposed, but the original panettone still had to be shipped directly from Milan.

This gap was noticed by Carlo Bauducco, who had a small coffee shop in Turin selling coffee from Brazil. Thanks to his contacts, after trying to trade in bakery machines, he found himself in São Paulo, where he saw that the Italian community in Brazil represented a huge potential market ready to receive locally produced panettoni.

The panettone of Minas Gerais

Demonstrating considerable entrepreneurial spirit, Carlo Bauducco moved to Extrema in the state of Minas Gerais with his family. He brought along pastry chef Armando Poppa and a piece of sourdough, the ancestor of all future panettoni: in 1950, the first example of a long series was baked in Extrema. Today, Bauducco is the largest panettone producer in the world, with an annual production of 80 million pieces exported to 50 countries, from the United States to Japan. Thanks to this company, Brazil leads the world panettone market with approximately 200 million pieces, followed by Peru and Italy, which ranks third with 50 million panettoni produced annually.

The strength of Made in Italy

Although Bauducco is little known in our country, it has nothing to do with the "Italian sounding" phenomenon. On the contrary, it is the highest expression of the success of Italian entrepreneurship abroad. Thanks to standardised production processes and competitive prices, Bauducco has managed to transform a national speciality into a product known and appreciated worldwide, representing Made in Italy at the highest level.

The "Panettone Made in Peru"

The "Peruvian panettone" by D'Onofrio has a similar story and is also the product of Italian entrepreneurial success. In the late 19th century, 21-year-old ice cream maker Antonio D'Onofrio left Caserta for South America, where he eventually headed an empire of ice cream and sweets. The business was continued by his son Antonio and later sold to a branch of Nestlé in 1997. Proudly Peruvian, the brand claims Italian origins and is deeply rooted in the South American country.

This photo and the opening one are by Francesco Vignali.

Tricolour tradition of quality

Despite the disparity in quantity, Italian panettone continues to be in demand abroad, thanks to the quality of the raw materials used and the care taken in its production. The strength of made in Italy is not only based on industrial production but on the continuous experimentation of innovative solutions aimed at improving the characteristics of panettone.

Artisanal production is experiencing steady growth, thanks to Italian master pastry chefs who continue to advance the sector of large leavened goods. A tradition with over two centuries of history, which has helped maintain Italy firmly at the top for the quality of its panettone.

It's the year of Barbera. We recommend an excellent one with the best value for money

It's the year of Barbera. We recommend an excellent one with the best value for money The best Orange Wines to gift this Christmas, selected by Gambero Rosso

The best Orange Wines to gift this Christmas, selected by Gambero Rosso The historic Neapolitan chocolatier built by a gentleman and his wife

The historic Neapolitan chocolatier built by a gentleman and his wife In Turkey, the Michelin Guide Awards also recognize an Italian restaurant—but not with a Star

In Turkey, the Michelin Guide Awards also recognize an Italian restaurant—but not with a Star An interesting Japanese fine dining restaurant near Turin

An interesting Japanese fine dining restaurant near Turin