Ragoût, as the name suggests, originates in France, but the initial seventeenth-century versions were quite different from today’s. These were stews made with fine ingredients such as mushrooms, truffles, sweetbreads, rooster combs, chicken livers, artichoke hearts, lemon slices, and so forth, prepared on a base of vegetables and thickened with butter and flour. There are dozens of such recipes used to flavour roasts and meat stews, such as "Pollastre in ragù" (Hen in ragù), "Spalla di vitello in ragù" (Veal shoulder in ragù), or "Lingua di maiale in ragù" (Pork tongue in ragù).

The Ragout de bœuf et pommes de terre, a French classic. Photo by Arnaud 25 (Own work, CC-BY-SA-4.0) from Wikipedia

The French ragoût trend of the 17th century

The very word ragoût comes from the old French ragoûter, meaning "to awaken taste," which perfectly summarises its role. Ragù soon became one of the symbols of the new culinary fashion. Along with concentrated broths and creamy sauces, it marked the French culinary revolution, replacing the range of flavours based on medieval spices. Cinnamon, cloves, ginger, and nutmeg were abolished or used only in minimal quantities, while sugar shifted to the end of the meal and was no longer scattered over savoury dishes.

One hundred years later, ragù arrives in Italy

The new French delicacies, however, alarmed physicians who accused chefs of preparing dishes harmful to health. Ragù, in particular, became the target of fierce criticism, as expressed in Cuciniera piemontese (The Piedmontese Cookbook) of 1771: "They are harmful to health because they provoke in us violent fermentations which corrupt our humours and cause the firm parts of the body to lose their elastic virtue, eventually destroying the principles of life.” It is unclear what these "firm parts of the body" might have been, but the physician would have certainly advised against them.

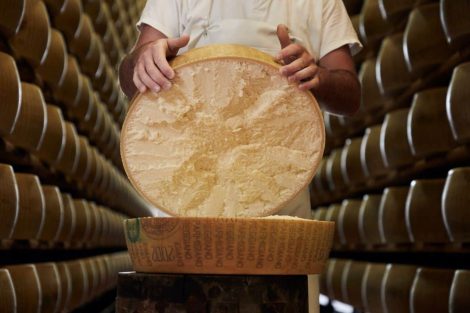

Bolognese ragù ingredients

Rome and Naples: early fans among the clergy and nobility

Among the first to embrace the culinary novelty was Antonio Latini, once chef to Cardinal Barberini in Rome and to Esteban Carillo Salsedo, the prime minister of the Viceroy of Naples. From his vantage point overlooking Vesuvius, Latini wrote Lo scalco alla moderna (The Modern Steward) in 1692: this cookbook features many innovations, including the first mention of "Salsa di pomadoro, alla spagnuola" (Spanish-style tomato sauce), though it is not yet a ragù.

Thanks to him, ragù made its debut in Naples – or rather, raù, as he called it in his recipe "Piatto detto Raù" (Dish called Raù) – which still did not feature tomato. If you think it’s anything like the ragù of today, though, you’re mistaken. In fact, it was a stuffed veal flank filled with minced meat, egg yolks, black cherry pulp, ham, marrow, truffles, mostaccioli biscuit crumbs, pine nuts, aromatic herbs, and spices, which was baked and served with a separately cooked stew (the actual ragù) of sweetbreads, cauliflower tops, and asparagus.

The first Italian encounter between ragù and pasta

It would take several decades for ragù to meet pasta, and naturally, this meeting took place in Italy. Initially, it would happen through timballos – those rich dishes encased in a pasta shell that the French filled with meat, while Italians crammed them with macaroni and lasagna. Baked pasta was the star of the time, sharing the stage with pasta served in broth. Dry pasta, on the other hand, was less common, and its condiments were still limited to just butter and grated cheese, with very few exceptions.

This was also how pasta was eaten in Naples, at least until the mid-eighteenth century. It was in the midst of the Enlightenment that something began to change. To the simple butter-and-cheese seasoning, an extra flavour was added: a few spoonfuls of the sauce obtained from a meat stew. Thus was born what would be called sughillo, used to give pasta more flavour, a true ancestor of all Neapolitan ragùs. It is first referenced by none other than Giacomo Casanova. In his memoirs, he tells of having served "maccheroni al sughillo" at his villa outside Paris during his stay between 1757 and 1758. Besides being a great seducer, Casanova was known as a lover of fine food, so it is no surprise that he was the first to introduce the recipe beyond the Alps.

Neapolitan Maccheroni: veal and vegetable sauce

To find a real recipe for "Maccaroni alla Napolitana" (Neapolitan Maccheroni), we have to wait until the end of the century and the publication of Francesco Leonardi’s treatise, the most important chef of the 18th century. In his L’Apicio Moderno of 1790, he seasons freshly drained macaroni with grated Parmesan and pepper, to which he adds "Veal sauce, or beef, or a good stew broth, or clove broth." The primary seasoning was still Parmesan-based, somewhat like an early cacio e pepe, with sauce added on top. In lieu of the broth from a large piece of stewed meat, Leonardi suggests using veal or beef sauce obtained by browning meat and other ingredients, finishing with a robust broth. The result is a brown liquid with intense roast meat and vegetable aromas, one of the cornerstones of 18th-century cuisine.

Sandwich with Neapolitan ragù from Salumeria Upnea in Naples

The birth of the "true" Neapolitan ragù

In the second edition of 1807, the recipe was modified to include tomato among the stew ingredients. This was one of the very first appearances of tomato in a sauce dedicated to pasta – a marriage that would never be dissolved again and represents one of the most successful and enduring unions in modern cuisine.

Ten years later, in 1817, one of the most important Neapolitan cookbooks of the century was published, entitled *Cucina casereccia* (Homemade Cooking), authored by someone who signed only with the initials M.F. Thanks to him, we have a description of the first true prototype of ragù that would be passed down with very few variations until the 1960s. It is quite a record, considering these were revolutionary years for Italian cuisine.

Naturally, the recipe for "Maccheroni alla napoletana" is included, which, once drained, "are loaded with old cheese, and grated caciocavallo, and are prepared with good ragù broth, in which tomatoes are cooked at the appropriate time, or with their concentrate."

The stew-maccheroni duo is a recurring theme in all the "menus" published in cookbooks. Every time a large piece of meat was stewed, the sauce was used to dress the maccheroni: the stew was the main course, and the maccheroni were a side dish. But from this point on, these elements would play an increasingly important role in the Neapolitan diet.

The legend of "O’raù" by Eduardo De Filippo

By the 1960s, Eduardo De Filippo put on the play Sabato, domenica e lunedì, centered around the preparation of the classic ragù. The curtain opens on Donna Rosa in the kitchen, featuring "a five-kilogram piece of neck" cooked with a large amount of onions and a little tomato.

The traditional recipe, however, was changing, and within a few years, pork meat would be introduced – an ingredient previously excluded. After a long period of stagnation, Neapolitan ragù experienced a rapid evolution that it had been spared until then. Today’s recipe includes a part of beef, usually chuck, with added pork ribs, sausages, as well as the classic braciole (beef rolls filled with grated pecorino cheese, garlic, parsley, pine nuts, and raisins). Neapolitan ragù has grown increasingly rich, and the variations are endless, both in cookbooks and home versions, where the secrets never leave the household.

Bologna: the practicality of minced meat

Ragù in Bologna, on the other hand, starts fully developed. It is unclear whether this is due to a lack of historical sources describing its early steps or because it originated from earlier recipes that used minced meat to flavour pasta. The major difference lies here: while Neapolitan ragù traditionally uses only the liquid portion on the macaroni and the stew is eaten separately, in Bolognese ragù all the minced meat ends up on the plate. This was a method of making the pasta heartier, freeing it from the need to prepare a large piece of meat just to dress the macaroni. Practicality is the true innovation of the “Bolognese” style.

Pellegrino Artusi’s Maccheroni alla Bolognese

The first to discuss it is Pellegrino Artusi, the celebrated Romagna gastronome, in his 'La Scienza in cucina e l'arte di mangiar bene' (1891). Artusi never uses the word “ragù” in the cookbook for two good reasons: firstly, the term still referred to the old meat dishes in sauces, and secondly, he was allergic to French words and fought for the Italian-ness of the language as well as the cuisine. For this reason, the recipe is titled “Maccheroni alla Bolognese,” while tagliatelle (the pasta shape most beloved by the Bolognese) are only mentioned as an alternative.

The first Bolognese Ragùs, with barely any tomato

Artusi's Maccheroni alla Bolognese, compared to today’s, did not include tomato but rather broth, with which the meat was “pulled” after the initial browning. This trait recalls how meat sauces were made in the previous century. What the two ragùs had in common was the initial dressing of the pasta with grated Parmesan cheese. Even at the end of the 19th century, cheese remained the primary ingredient, while the ragù was an addition. The macaroni was sprinkled with plenty of Parmesan and topped with a few spoonfuls of ragù — quite the opposite of today’s method.

Ada Boni and her Talisman: a spoonful of tomato

Thanks to the fame reached by Artusi, in the following years the recipe was taken up and modified by numerous cookbooks. In the early 20th century, tomato sauce started to be added, but in small amounts: in the 1930s, Ada Boni in her *Talisman of Happiness* mentions “a coffee spoonful — no more — of tomato paste.” By the middle of the 20th century, pork meat was introduced, bringing the recipe to its current form.

Spaghetti Bolognese, a worldwide success

Artusi recommended using large macaroni known as “horse’s teeth,” while tagliatelle remained only a secondary option. Despite this, it would be tagliatelle all’uovo that would become the primary shape for this sauce. However, in 1898, just a few years after Artusi's cookbook was published, we find the first evidence of “Spaghetti di Napoli alla Bolognese,” as written on the menu at the Hotel Ville de Bologne in Turin. The pairing – which so angers Bolognese purists – can be said to have preceded tagliatelle with ragù. In Italy, this combination enjoys mixed fortunes, while in the rest of the world, “spaghetti Bolognese” (or bolognaise) remains one of the most beloved specialities today.

The classic Neapolitan Genovese with broken ziti

The “Mystery” of the most neapolitan Genovese

There is another ragù made with onions (lots of onions) and stewed beef that is used to dress the traditional ziti, broken by hand. Although it is a Neapolitan recipe, it is known as “genovese,” and this strange name has sparked all sorts of fantastical theories. Theories range from the idea that the dish originated in the port taverns of Naples during the 15th-century Aragonese rule, where the owners were Genovese, to a supposed Neapolitan cook nicknamed “O’ Genovese.” The solution, however, is much simpler and can be found in a few 19th-century cookbooks.

As we have seen, at the end of the 18th century, Francesco Leonardi described the recipe for maccheroni alla napoletana dressed with the stewed meat jus without tomato. This “white” version was the same used for lasagne alla genovese, which would spread shortly thereafter. By the mid-19th century, there was thus a single stew sauce with onions used for both Neapolitan macaroni and Genoese lasagne.

Genovese pesto becomes “The Ligurian Ragù”

Soon after, tomato began to be added to this sauce in Naples. After all, the city had an ancient bond with the fruit from the Americas, which was gaining popularity. For a time, Naples had two dressings for macaroni: one with tomato and one without. Since the latter was also known as “genovese,” Neapolitans decided to continue using this name for the “white” version only, while the one with tomato became the true “Neapolitan” version. Even in Genoa, this sauce for lasagne had a counterpart, a completely plant-based version intended for “lean” periods when meat was prohibited: Genoese pesto. Over the decades, the onion-based stew sauce faded away in Liguria, leaving room for pesto, which would become one of Genoa’s most iconic dishes. This is the reason why, and for no other, Naples has a “genovese” that has no equivalent in Liguria.

How Ragù helped Italian pasta conquer the world

When we think of pasta and its worldwide success, we forget a fundamental fact. Macaroni and spaghetti have existed since the Middle Ages, but their consumption was always limited as long as they were dressed only with butter and cheese. For almost half a millennium, pasta was not eaten any other way, while today there is an incalculable variety of sauces. The turning point was that single spoonful of stew jus someone poured over it. If it hadn’t been for the meeting between French ragoût and Italian pasta, the world today might not have been the same.

Perhaps someone in the past had already tried to dress pasta differently, but the timing wasn’t right, and the spark hadn’t ignited. After ragù, pasta sauces multiplied. At first, it was a quiet revolution, entirely Neapolitan, with tomatoes and clams as described by Ippolito Cavalcanti in 1837; then the trend spread and became a wave. Every time you eat pasta, whatever it may be (except for cacio e pepe), know that its success owes everything to ragù.

The alpine hotel where you can enjoy outstanding mountain cuisine

The alpine hotel where you can enjoy outstanding mountain cuisine Io Saturnalia! How to celebrate the festive season like an Ancient Roman

Io Saturnalia! How to celebrate the festive season like an Ancient Roman The UNESCO effect: tourism is growing, but there is a risk of losing identity

The UNESCO effect: tourism is growing, but there is a risk of losing identity The perfect pairing? Wine and books

The perfect pairing? Wine and books 2025 was the year of Trump's tariffs – will 2026 be better for Italian wine in the US?

2025 was the year of Trump's tariffs – will 2026 be better for Italian wine in the US?