by Anna Muzio

Don't just call it oil, or olive oil if you're lucky. Even extra virgin isn't enough. Where does it come from, where did it grow, how was it extracted? And how much does it cost? The correct price, first of all: according to recent debates, if Minister Francesco Lollobrigida thinks €30 per litre is a fair price for good oil, former senator Toninelli calls it "total madness." An oil importer says: people make a fuss about buying extra virgin olive oil at €20 per litre, yet when you service your car, the oil they use costs 50% more. You put olive oil into your body: shouldn't you be more willing to spend more on what's good for you than what's good for your car? Right? In theory, it's clear and obvious. Yet this is the paradox of products that are (apparently) too well-known, too familiar, always on our tables: we take them for granted, think we know them without really knowing much at all. And we expect to pay little for them without questioning what we bring home.

This is the battle for quality that underpins the work of Fioi, the Federazione italiana ovicoltori indipendenti (Italian Federation of Independent Olive Growers). They've made "small but good" their credo and manifesto. We discussed this with president Pietro Intini.

From bread to coffee to oil, the price debate cycles around: it's all fair, but good ones cost too much. Must we resign ourselves to the fact that only the rich can afford to eat well?

It's a matter of values. A clean extra virgin olive oil, not an excellence with a high polyphenol content, cannot cost less than €15 per litre in Italy today, especially considering the production declines and erratic weather conditions in recent years. I don't think it's such a big effort, considering that a bottle of oil can last a couple of weeks and, in the end, costs as much as a coffee a day.

Are there products that must be cheap? It's also a cultural issue.

It's the awareness that it's right for you, your child, and the ecosystem. It's a value scale, a perception of what matters; it's an economic but also a cultural issue. Of course, those who can't afford it must make compromises, which is normal.

Small and independent also means traditional. Do you look back to a golden age of olive growing?

We fiercely defend "traditional" olive growing, but by this, we don't mean farmers harvesting olives with ladders. We're open to technologies, but we defend biodiversity and promote it because people don't realise that Italy has over 550 varieties of olive trees—an incredible heritage. Yet, we often only talk about olive oil without even getting to the extra virgin designation, so the message and how it's communicated are important.

Behind the term EVO oil, there's a whole world.

In recent decades, olive growing has been taken over by intensive models using hybrid varieties, cultivated on several thousand trees per hectare with mechanical harvesting. This system maximises resource exploitation, requiring water, chemicals, and controlled environments. By traditional olive growing, I mean attachment to the land and its protection. But today, we do what my grandfather couldn't: with today's technologies, we produce the best EVO oils ever made in the millennia-long history of olive growing. Entering a quality mill, you're amazed by the research and technological investments necessary to make great oil.

Like what?

We've adopted many techniques from the wine world: we use nitrogen even in preservation, we filter—this is a Fioi foundation—our products must be filtered, stored in stainless steel at controlled temperatures under nitrogen. In the last five years, cold technology has developed because, for example, in Puglia, I harvest in mid-September at 30 degrees. You can't produce cold-pressed oil. The olives are stored in refrigerated cells, then washed with conditioned water at 5-6 degrees to bring the olives to the ideal temperature. This allows lipoxygenase development, enabling enzymatic reactions that would otherwise be blocked or lead to fermentation or bad odours. The evolution that wine has undergone and that oil is beginning to take is to make fragrant and objectively high-quality oils because not all EVO oils are the same. In oil, PDOs and PGIs contribute very little, showing there's no real attachment to origin. In the end, 95% of EVO oil is made for mass distribution with extra-EU or EU olives. That's the olive oil market. Within Fioi, there are companies that began raising the quality level twenty years ago, but consumer awareness must also increase: without both, there's no way out.

What are the steps to ensure quality?

We talk about production resulting from careful monitoring of the entire supply chain, starting from cultivation and meticulous selection of olives, with harvesting that respects the different ripening times each variety has. In case of blending, each variety is processed separately and only then assembled. Independent Olive Growers value their olives by bottling them and signing them with their name, a valorisation process that makes the grower aware of what they produce.

Most EVO oils on the market are "ambiguous." Why?

They come from oil that the oil industry collects from numerous cooperative mills that sell bulk oil, forming large batches that the industry assembles and bottles. In these huge assemblies, the aromatic and chemical characteristics of artisanal quality oil are completely lost because the raw material underwent no selection at the origin and was processed without the necessary criteria for quality oils. This leads to recurring scandals, with consumer protection associations conducting sample tests revealing characteristics not matching the declared product category, with organoleptic defects and chemical parameters unsuitable for EVO classification.

In Italy, there's the paradox that oil is insufficient for our consumption, yet olive farms are closing. Why?

Because olive growing needs to make a leap to valorise the product of its land and trees. Producing mediocre and banal oil and delivering it to a chain that does the same creates a product for bottling groups with no connection to the production chain. For them, added value is price; for us, it's everything behind it. We try to maintain the land that's being abandoned, as olive groves are left untended despite the product demand. We aim to spread the message to consumers and producers who don't value their product, telling them to name their bottle and focus on quality. Only then can they be economically sustainable and protect their landscape.

Meanwhile, the Xylella drama continues.

Currently, there are only four resistant varieties, two hybrids and two Italian varieties. We at Fioi are trying to shift research focus onto our rich olive heritage, hoping these two become ten. We have nothing against hybrids and crosses with Spanish varieties, but we'd like to see resilience and resistance research with our varieties because they have an Italian, distinctive matrix. Not out of parochialism, but because we need to value what's ours; otherwise, we'll lose our heritage and align our production with Spain's, the world's leading producer and exporter. A highly respectable nation, but we are something else.

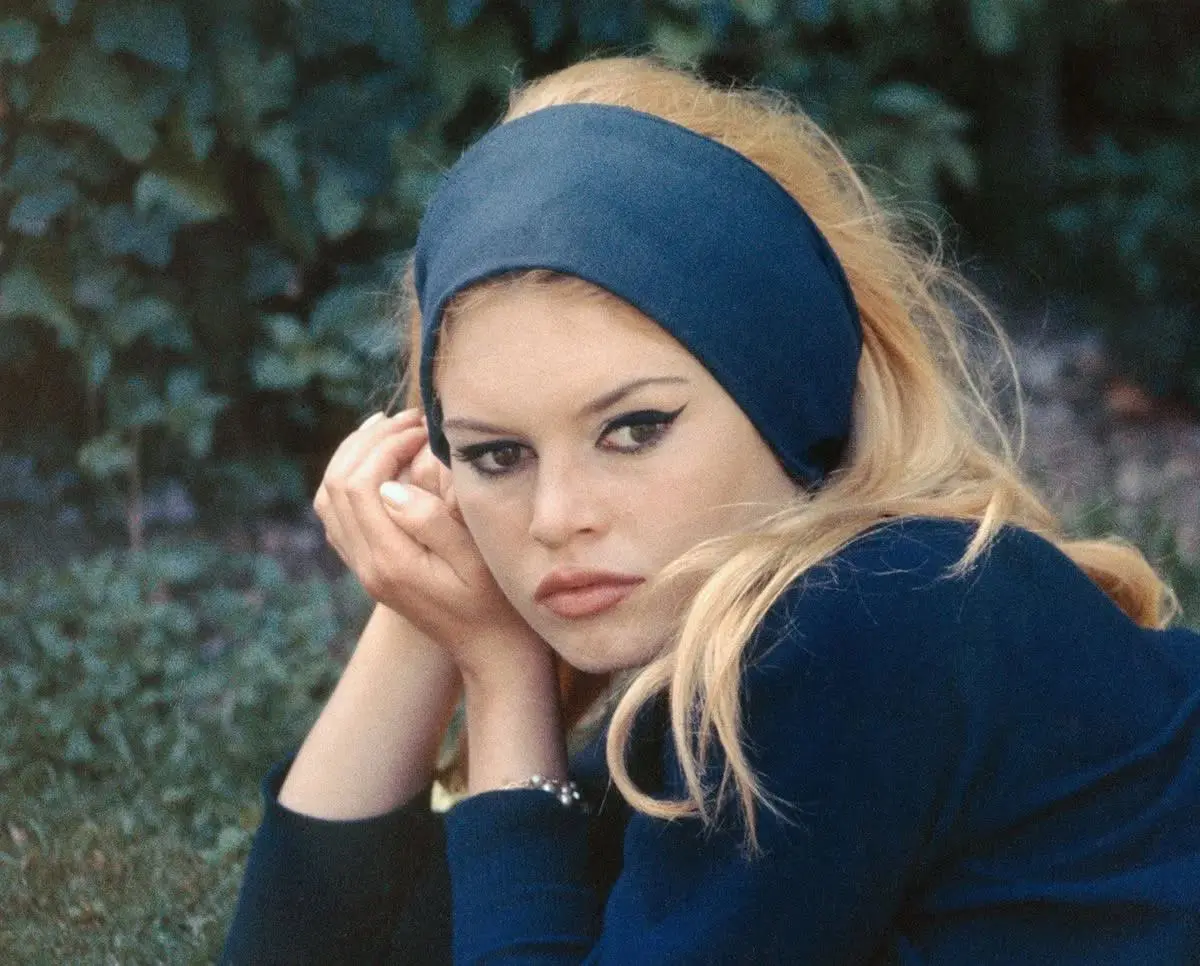

Brigitte Bardot’s final rosé: the wine that marks the end of an icon

Brigitte Bardot’s final rosé: the wine that marks the end of an icon What you need to know about Italy's new decree on dealcoholised wine

What you need to know about Italy's new decree on dealcoholised wine Why Arillo in Terrabianca's organic approach is paying off

Why Arillo in Terrabianca's organic approach is paying off What do sommeliers drink at Christmas?

What do sommeliers drink at Christmas?