By Simona Sirianni

Regardless of one's position, the impact of intensive farming on the environment due to emissions from each structure where animals are kept, among other factors, is undeniable. How to solve the problem is a constantly debated issue, also because opinions could not be more different: there are breeders who advocate for its benefits and breeders who, instead, have chosen a path more inspired by ecological issues. There are animal rights activists, who prioritize the ethical issue of suffering inflicted on sentient living beings. And there is science, which deems synthetic meat as exceptional instead of steak.

Pythons instead of Chianine?

Among the various theses, there are also some new researches recently published in the journal Scientific Reports that suggest a new solution: the breeding of pythons as a practical alternative to conventional livestock farming, especially in those regions of the world where the climate crisis, pandemics, and extreme land use are threatening food production. Leading the studies on some farms of this species of snakes in Thailand and Vietnam and explaining that "based on some of the most important sustainability criteria, pythons are superior to all traditionally farmed and studied species so far," was Dr. Daniel Natusch, a researcher and President of the IUCN Reptile Specialist Group, the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Sustainable alternative snakes

What would these parameters be, it is soon said: essentially, pythons generate fewer greenhouse gases, require less water than warm-blooded animals, are more resistant to extreme weather conditions, and do not transmit dangerous diseases, such as avian influenza or COVID-19. Not to mention that in addition, reptiles have proven to be a more efficient source of protein compared to poultry, pigs, cattle, and salmon. In short, for the Australian professor, the python would be the perfect solution to end all the problems caused by intensive farming.

The need for protein is growing

With perhaps too much enthusiasm, Natusch makes some considerations that should be taken into account: according to the professor, in fact, if there is still little talk about the benefits that would be obtained by replacing the classic Chianina with snake meat, it is not because there are none, but rather because the conventional system tends to still defend intensive farming. A real shame, especially considering the food shortage that continues to compromise the health of millions of children in the poorest regions of the world and where the need for high-quality proteins is skyrocketing.

Just think about the cattle that collapse in the fields due to unprecedented droughts that have hit Africa and at the same time think about how reptiles could represent a turning point for livestock by being able to regulate their own metabolic processes and maintain the body in good condition even during the worst famines.

"Some of the pythons in our study stopped eating for four months - 45% of their existence - with no repercussions on their physical condition," recounted the co-author of the document, Dr. Patrick Aust, an ecologist living in Africa, adding "let's try to imagine not feeding a chicken for four months: after four or five days, it would already be dead."

A reptile in exchange for a roast

Natusch and Aust have few doubts and are convinced of the results of their research and that pythons could really mean a breakthrough for more sustainable meat production. On the other hand, they argue, with the worsening of global food security due to climate change and the agricultural sector that will suffer from the spread of infectious diseases and the decrease in natural resources, there is no doubt that reptiles will become a compulsory alternative at that point.

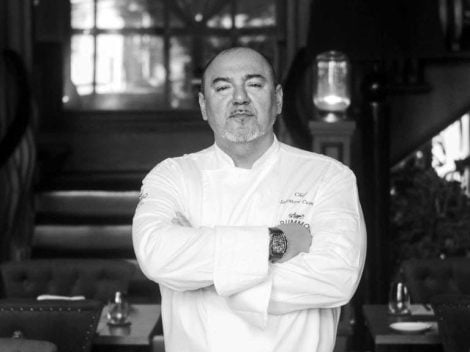

It is difficult to say how many people would be tempted to give up a tasty roast to eat snake meat. Let's say that with insect flour, we are not doing very well. Consumers' curiosity is there, but there is also a sort of disgust for a product that, if in other cultures is already sometimes considered a valuable food, in the West struggles to obtain the same approval. It is true, however, that if the most frequent reaction to new foods such as insects is the rejection of their use, among Michelin-starred chefs or not, there are those who are more open-minded and at least open to experimenting with new dishes: among them is chef Loris Caporizzi, who is also an expert in entomophagy, who has long been proposing dishes based on insects, believing that "identifying alternative food sources is no longer a choice, but it is now a necessity."

A completely opposite position is that of chef Enrico Derflingher, since 2014 Ambassador of Italian Cuisine, according to whom the rejection is essentially due to a cultural issue: without, in fact, disdaining at all to eat snakes, bees, crickets, or other insects, also tasted around the world, Derflingher has clearly stated that such animals "will not enter his kitchen." And not because of their bad taste, but because they have nothing to do with our history, cuisine, and tradition.

Where to eat at a farm stay in Sicily: the best addresses in the Provinces of Trapani, Palermo, and Agrigento

Where to eat at a farm stay in Sicily: the best addresses in the Provinces of Trapani, Palermo, and Agrigento Wine in cans, bottle-fermented, and alcohol free: the unstoppable change in Gen Z’s tastes

Wine in cans, bottle-fermented, and alcohol free: the unstoppable change in Gen Z’s tastes The great Bordeaux exodus of Chinese entrepreneurs: around fifty Châteaux up for sale

The great Bordeaux exodus of Chinese entrepreneurs: around fifty Châteaux up for sale Dubai speaks Italian: a journey through the Emirate's best Italian restaurants

Dubai speaks Italian: a journey through the Emirate's best Italian restaurants In France, over a thousand winegrowers have decided to abandon wine production

In France, over a thousand winegrowers have decided to abandon wine production