Gualtiero Marchesi is regarded as the father of modern Italian cuisine. In 1977, already in his 40s, he opened his first restaurant, which became famous not only for its excellence but also as the training ground for many great chefs of the next generation. Carlo Cracco, Davide Oldani, Andrea Berton, Ernst Knam, and many others—collectively known as the Marchesi boys—are among them. Marchesi was more than just a chef; he was a forerunner and innovator in Italian cuisine, catapulting the concept of Italian fine dining onto the global stage. His dishes have become iconic. Who doesn’t know the open raviolo or the saffron and gold risotto? To pay tribute, we’ve put together a journey through his ten most significant creations.

The 10 iconic dishes of Gualtiero Marchesi

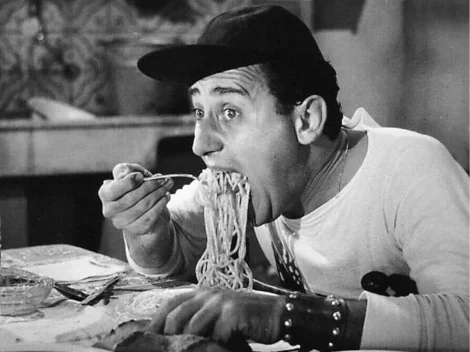

Spaghetti Salad with Caviar and Chives – 1980

A true icon of Italian dining, pasta was an obsession for Marchesi. Initially dismissed as chaotic and excessive—a quantitative remnant of poverty—it was eventually redeemed. Serving as a complement and support to other elements, pasta in these spaghetti and caviar reflects Marchesi’s interpolation principle, a dialogue between high and low motifs. Particularly noteworthy is the cold serving temperature, which highlights the sturgeon roe’s savoury qualities, evoking memories of Japan. Finally, this dish transforms a classic main course into a starter.

Italian Sushi (One-Act Fish) – 1980

“The craze for Japanese cuisine? Just flip through an old issue of Gambero Rosso to discover it dates back to 2002–2003,” claims Ferran Adrià, who credits himself for its popularity. Wrongly so, as Japanese elements had long informed Marchesi’s cuisine, drawn eclectically from various sources, much like today’s chefs. Even Moreno Cedroni, who delved deeply into Italian “susci,” acknowledged Marchesi’s influence.

Saffron and Gold Risotto – 1981

The ultimate icon of Gualtiero Marchesi, the undeniable father of new Italian cuisine. The recipe involves a specific method, passed down to many disciples (such as the use of acidified butter in the final stirring, replacing much of the Grana cheese to impart acidity). But it’s the beauty that mesmerises: the contrast between the circular and square forms, inspired by Japanese aesthetics; a black border and a golden heart that sanctify tradition, reminiscent of a shimmer in an iconostasis, marking a transition into another realm. “The typical is also mythical,” wrote Thomas Mann.

Open Raviolo – 1982

A masterpiece born by chance, inspired by a friend’s story about eating an improperly sealed raviolo at a banquet. “Although it was a criticism, the word ‘open’ related to ravioli kept spinning in my head until it inspired a new dish.” The concept involves quick cooking for both the pasta and the filling—be it scallops for seafood or kidneys and sweetbreads for meat—highlighting their textures. It also breaks the traditional barrier between the pasta and the sauce, predating Ferran Adrià’s research. Echoing Umberto Eco’s Opera Aperta, it represents a breaking open of tradition, revealing new interpretive possibilities.

Cuttlefish in Ink – 1983

Cooking by subtraction rather than addition was a fundamental lesson from Marchesi. Like Michelangelo, he believed that the material inherently contained its finished form, which the chef must decipher and bring to life. This approach is exemplified in the cuttlefish in ink, comprising poached cuttlefish and a butter-mounted ink sauce. The natural elegance of the tentacles and body shines, in line with Japanese aesthetics, which oppose the geometric tendencies of European schools.

2000 Milanese Cutlet – 1991

Another masterpiece inspired by Italy’s regional repertoire, illustrating Marchesi’s belief that “novelty arises by rearranging elements of the past.” Here, the Milanese cutlet is thickly cut, cubed, breaded, and fried, combining playful presentation with food design principles. The cubes eliminate the need for knives, maintain the crispness of the crust, and optimise the meat-to-breading ratio—a true gourmand’s delight.

Pressed Duck – 1993

Everything, its opposite, and the opposite of its opposite—Marchesi’s unique style encapsulated. The 1990s marked Marchesi’s departure from nouvelle cuisine, embracing classic service styles for dishes unsuited to standard plating. An example is duck à la presse, revived with tableside pressing. This “total cuisine” concept encompasses product, preparation, service, and spans past, present, and future. Another prescient innovation was the Lazy Susan-style serving by his protégé Lopriore: elaborate dishes served centre-table in heated silverware, reminiscent of the late Andrea Salvetti’s workshop.

Fish Dripping – 2004

“In painting, as in cooking, one must let something fall somewhere. As it falls, the substance transforms: the drop spreads, and the food becomes tender, creating new matter,” wrote Roland Barthes about painter Réquichot, boldly paralleling major and minor arts. This concept underpins this revolutionary dish, inspired by Jackson Pollock. Borrowing the painter’s gestures, Marchesi applied them to various sauces, where colour becomes taste, essence, and emotion.

Four Pastas – 2006

Over time, pasta shed its supporting role to become the protagonist, exemplified by Four Pastas. This dish reflects the revolutionary food design concept implicit in the diverse shapes found in every Italian pantry. The focus shifts to the “form of flavour,” as described by Davide Scabin, with minimalist condiments of oil and Pecorino—an inseparable duo for Marchesi, like butter and Grana. Materiality and minimalism point to “less cooking,” with an artistic nod to Andy Warhol as the spark of inspiration.

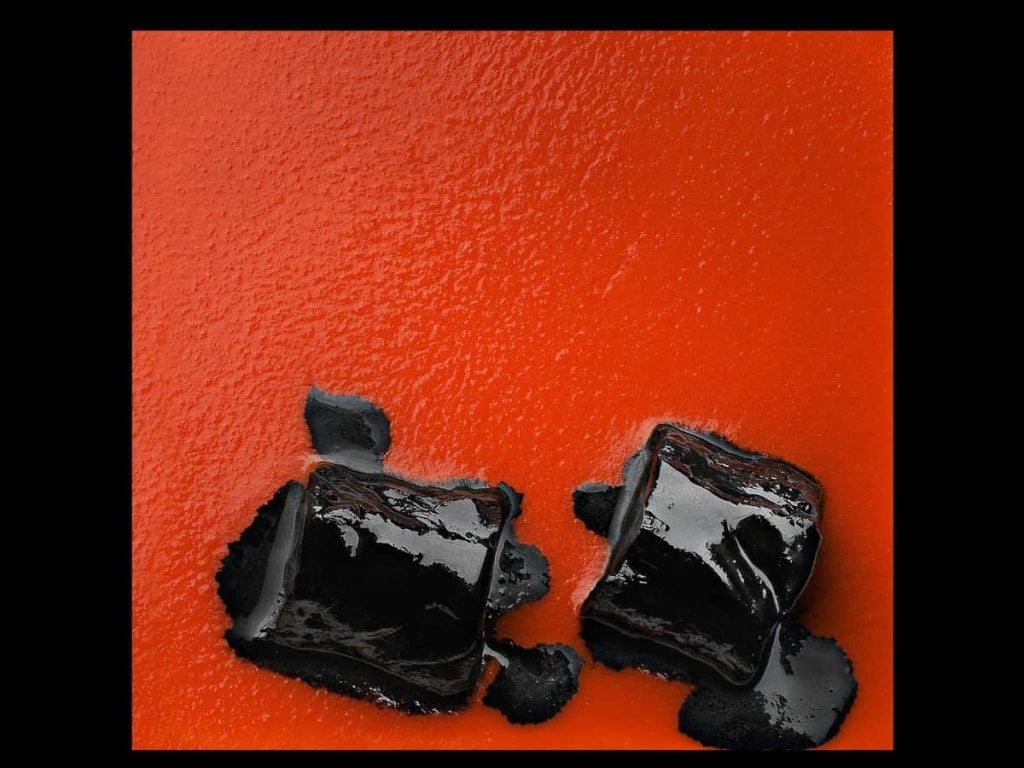

Red and Black – 2011

“Marchesi’s revolution was, above all, aesthetic,” asserted the renowned gastronomic photographer Bob Noto. Long before Massimo Bottura, and following in the footsteps of Cipriani’s Carpaccio, Marchesi consistently drew from the visual arts, cultivating a painterly approach. One example is this homage to Lucio Fontana (another artistic nod was Egg à la Burri in 2007), where the plate becomes a canvas for contrasts that explode on the palate. Dominating is the materiality of colour in an aleatory arrangement born from the interaction between gazpacho sauce and squid ink mayonnaise, embodying another Japanese aesthetic tenet: that a dish should remain beautiful while being eaten.

Veronafiere closes 2024 with its best-ever financial results and confirms Federico Bricolo as Chairman

Veronafiere closes 2024 with its best-ever financial results and confirms Federico Bricolo as Chairman Not just Passito: it’s dry Malvasia driving the wine economy of the Aeolian Islands

Not just Passito: it’s dry Malvasia driving the wine economy of the Aeolian Islands In the United States, it’s Prosecco mania – despite Trump’s tariffs. And the credit goes to women

In the United States, it’s Prosecco mania – despite Trump’s tariffs. And the credit goes to women In Romagna, there's an osteria opened in an old rectory that has breathed life back into a depopulated village

In Romagna, there's an osteria opened in an old rectory that has breathed life back into a depopulated village Dining with the Cardinals: here’s what they eat during the Conclave

Dining with the Cardinals: here’s what they eat during the Conclave