Marius arrived in Gorgona a couple of years ago. Early in the morning, he goes to the vineyard with Saber and Daniele, and at the right moment, he heads to the cellar. The three are employees of the Frescobaldi winery, which manages the island's vineyards, located an hour's sail from Livorno. The island spans 200 hectares, terraced up to 220 meters above the sea, with rows of vines and olive groves, pastures, and gardens. Gorgona is the last remaining prison island in Europe. It houses 81 inmates nearing the end of their sentences, more than half of whom are under Article 21, which regulates inmates' access to work. Here, they engage in agricultural activities, with wine production being the most well-known due to the collaboration with the Marchesi Frescobaldi, who have seven centuries of enological history. However, it is not the only activity: there are also olive groves and a bakery. A dairy was once operational but was shut down in 2020. All these activities are carried out by the inmates living here.

The Prisoners' Wine

Spending a day on the island – which can be visited – the beauty of these landscapes makes one forget that it is a detention center. The fences, though present, are not noticeable, the atmosphere is not oppressive, and the nature is enchanting. "When I'm working, I don't feel like a prisoner, just a winemaker. I remember I'm in prison in the evening when the doors close," says Marius. He is entrusted with an important role: he drives the tractor and handles all the tools, even those one wouldn't think permitted in such a context. It is about reintegration into society through trust and responsibility. "I have a commitment and responsibility that I didn't have before, outside prison." He still has 3 years and 8 months to serve but hopes to be released to work in a winery. "I've completed my journey here and in other prisons; now I hope to get closer to my family in Piedmont," a land of great wines. This is his path: he had never worked the land before, and the beginnings were not easy, with a lot of work to do and weeds to clear. "It was tough, but seeing the plants bloom and the vineyards come back to life, the satisfaction is immense. We are happy with the results, with what we have managed to produce." The journey has been long: "We learned from scratch, step by step. I believe that having grown with Frescobaldi can be a good calling card." He feels prepared, although one step is missing: the final one. Alcohol is forbidden in prison, so he has not yet tasted the fruit of his labor. He will do so when he is released; in the meantime, he continues his training, as do the other inmates. They all work on the island, learning a trade and building a new future for themselves.

The Celebration Day on Gorgona

Prison overcrowding is not a problem here: being on the island can be a dream or a nightmare for those who suffer from the double isolation of prison and geography. Requests for Gorgona are not enough to fill the entire facility. "Many, after a couple of months, asked to be transferred," says Marius, "they couldn't handle the island." The first three months were tough for him too. "In winter, the sea is rough, and no one comes. The island is not easy." However, this time of year is a moment of great celebration, as the new vintage of the island's wine is presented. The first harvest was presented in Rome, but since then, the event has always been held on the island. "The wine must be presented where it is produced," says Marchese Frescobaldi. It is thanks to him that so many people have come to know about the project. Initially, it was a small group, growing year by year. "Gorgona is something unique and special." This is evident as soon as one approaches, greeted by a handful of colorful houses and a bright blue wall with a blue inscription: "Penalties cannot consist of treatments contrary to the sense of humanity and must aim at the re-education of the convicted." This is Article 27 of the Italian Constitution. "We want it to be something concrete in Gorgona," says Giuseppe Renna, director of the prison, who, like his predecessors, believes in redemption and the possibility of taking a new path through work. The Frescobaldi family also strongly believed in this when they agreed to collaborate on this project over 10 years ago.

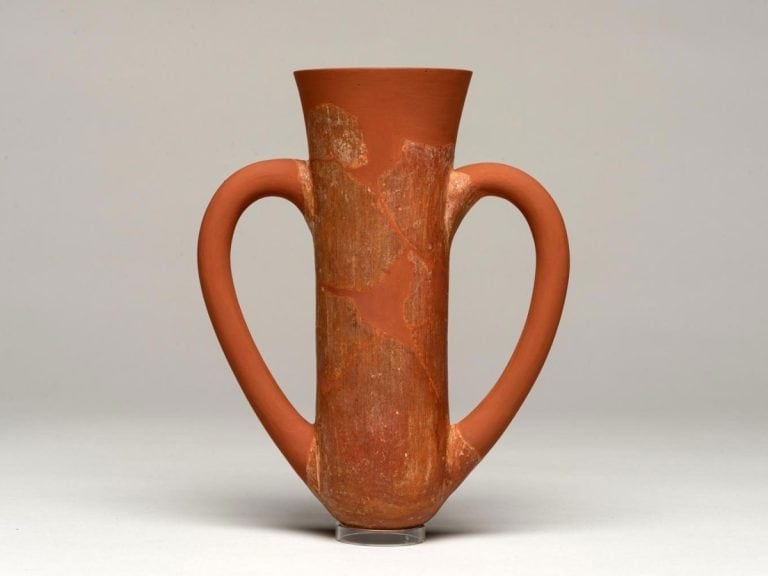

The first vineyards date back to 1999, a little over a hectare. A few years later, more rows were added. Today, there are 2.3 hectares of vineyards, mostly Vermentino and Ansonica, Sangiovese and Vermentino Nero, maintained according to organic principles, though not certified, and cared for by inmates along with agronomists and oenologists from Frescobaldi. Work in the cellar is kept to a minimum: indigenous yeasts, controlled temperatures. After vinification, there is a journey to the mainland for bottling: tractors, cranes, ships, and then roads to Florence. There, the bottles come to life: 9,000 a year. In 2015, Gorgona Rosso was also born from some rows of Sangiovese and Vermentino Nero, aged in terracotta. The goal is to produce a wine that has value regardless of the project behind it. And Lamberto Frescobaldi says with great satisfaction, "Many buy the wine without even knowing what is behind it." The human and social impact, the reduction of recidivism, and the demonstration that another detention model is possible are the added values. Since 2012, the project has involved around a hundred people, many of whom have had the opportunity to continue working at Frescobaldi. "Among our ventures, this is the one that has marked us the most," comments Marchese Lamberto.

Gorgona: attractive and wild wine

The result of all this work is a wine that is a child of light, sea, and wind, which is also the theme of this year's label: Grecale, Scirocco, Libeccio, and Maestrale, fundamental elements in Gorgona's viticulture. "This is a unique wine that represents the territory," a wine that is "attractive and wild," decisive, complex, and Mediterranean. It was paired with a lunch organized by the inmates themselves, guided by chef Fernanda Zazzera, in collaboration with eight inmates from Bollate prison, another model penitentiary with the InGalera project, the first and only restaurant inside a prison. An experience of recovery and reintegration: Bollate has the lowest recidivism rate in Italy, and in 21 years has given a perspective and paid work to 120 inmates. It should be clear to everyone that recovery and building a different future is the only valid form of penalty because it addresses a dual interest: that of the individual and that of society. Gorgona and InGalera testify to this.

Meloni: "Tariffs? If necessary, there will be consequences. Heavy impact on agri-food sector"

Meloni: "Tariffs? If necessary, there will be consequences. Heavy impact on agri-food sector" The Government honours the greats of Italian cuisine, from Bottura to Pepe. Massari: "Thank you, Meloni, the only one who listened to us"

The Government honours the greats of Italian cuisine, from Bottura to Pepe. Massari: "Thank you, Meloni, the only one who listened to us" "We must promote a cuisine that is not just for the few." Interview with Massimo Bottura

"We must promote a cuisine that is not just for the few." Interview with Massimo Bottura Wine was a drink of the people as early as the Early Bronze Age. A study disproves the ancient elitism of Bacchus’ nectar

Wine was a drink of the people as early as the Early Bronze Age. A study disproves the ancient elitism of Bacchus’ nectar "From 2nd April, US tariffs between 10% and 25% on wine as well." The announcement from the Wine Trade Alliance

"From 2nd April, US tariffs between 10% and 25% on wine as well." The announcement from the Wine Trade Alliance