Compared to a few decades ago, opening a bottle and finding a clearly faulty wine is quite rare. Technological and scientific advancements have undeniably improved winemaking, to the point that some wine diseases are now a thing of the past. For example, who can say they have recently tasted a wine affected by fioretta? Probably no consumer has even heard of it in the last twenty years.

This is a true wine disease that can be recognised at first glance. A white film forms on the wine, caused by the Candida Mycoderma yeast, which makes the wine taste flat and slightly vinegary. It is usually due to poor hygiene in production and maturation areas or improperly maintained containers (especially when they are not filled to capacity). These are aspects that modern wineries focus on far more than in the past.

That said, this does not mean that faulty bottles no longer exist on the market. Below, we outline the most common faults and how to recognise them.

The main wine faults

High volatile acidity

We have already discussed wine acidity in our glossary, where we mentioned that it is one of the product's main characteristics. Acidity can be divided into fixed, volatile, and total acidity. The first comes from various acidic substances in the wine and is perceived on the palate during tasting. Volatile acidity, as the name suggests, consists of molecules that disperse into the air. The sum of the two gives the total acidity of a wine.

The most important volatile acid is acetic acid. Within certain limits, volatile acidity can add character to wine, providing an energetic boost to both aromas and taste. However, when levels become too high, the wine is considered faulty. This is noticeable as both the aroma and taste resemble vinegar.

Brettanomyces contamination

Brettanomyces are yeasts found in soil, tree bark, grape skins, and wooden barrels that have not been properly cleaned. They multiply in the presence of oxygen and are resistant to alcohol, meaning they can thrive not only during the winemaking process but also during maturation and ageing.

As with volatile acidity, if Brett (as it is commonly abbreviated) remains within certain limits, it can add complexity and structure to wine. However, the risk of fault is high—controlling something as wild as Brett is nearly impossible.

So, what does a Brett-tainted wine smell like? The aromas can be extremely unpleasant, forming a veritable "horror gallery" of odours: wet dog, mouse urine, barnyard, horse saddle, plastic, paint, sweat, and cheese rind.

Oxidation

A wine’s interaction with oxygen plays a key role in its evolution, contributing to the complexity and appeal of its character. Maturation and ageing are essentially about allowing the wine to breathe slowly, enriching its profile with new nuances. However, when this interaction becomes excessive, problems arise.

Simply put, when exposure to oxygen is too strong—whether due to winemaking errors, a faulty cork, or excessive ageing—the wine begins to fade.

- Colour fades: White wines darken towards hazelnut brown, while red wines lose vibrancy and take on brick or orange hues.

- Aromas disappear: Fragrances vanish, giving way to solvent-like smells.

- Taste deteriorates: The palate experiences a drying sensation with a slightly bitter aftertaste.

That said, there is a specific category of wines that thrive on oxidation, turning it into an asset rather than a fault. These are oxidative wines, often complex and designed for slow contemplation. Examples include Malvasia di Bosa and Vernaccia di Oristano in Italy, and Vin Jaune from Jura in France.

Reduction

This is the opposite of oxidation. During the winemaking process, there are crucial moments when oxygen exposure is necessary—such as during the early stages of fermentation when yeast requires oxygen to initiate the process.

If oxygen supply is insufficient, poor fermentation can occur, leading to the formation of volatile sulphur compounds. These can also develop during ageing and after bottling. As a result, unpleasant aromas appear in the glass, resembling onion, garlic, matchstick, and in extreme cases, rotten eggs or boiled cabbage. On the palate, the wine may have an excessively bitter or overly vegetal taste.

Unintended refermentation

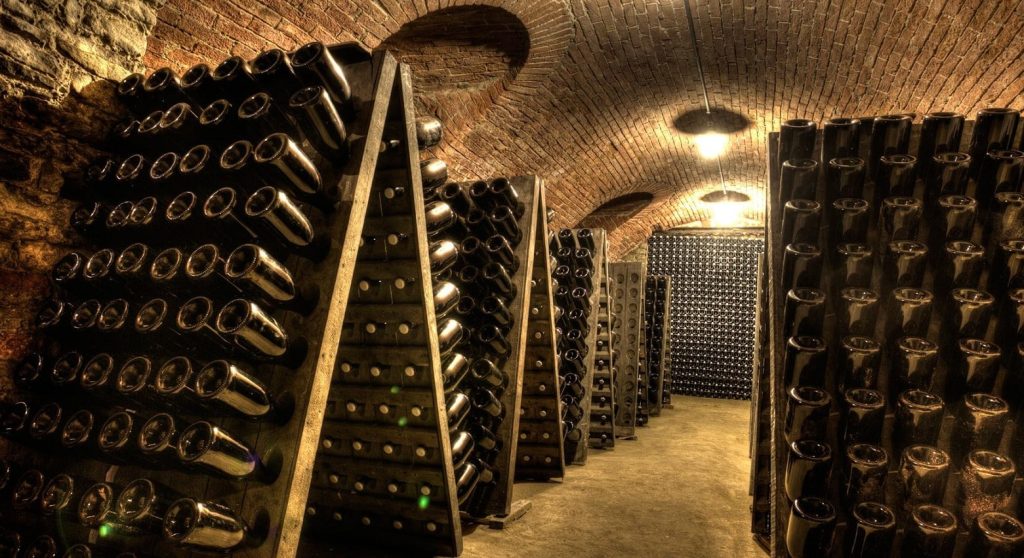

This fault refers to uncontrolled refermentation within the bottle. Some wines, such as bottle-fermented or ancestral method wines, as well as Méthode Champenoise sparkling wines, intentionally undergo refermentation. However, in other cases, it is an unintended flaw.

Why does unintended refermentation occur?

Typically, it happens when residual fermentable sugars remain in the wine alongside active yeast. If sulphites fail to halt fermentation, yeast can reactivate, restarting the process.

- On the palate: A slight fizziness due to carbon dioxide is noticeable. If the wine was meant to be still, this is considered a fault.

- On the nose: Aromas of yeast, raw bread dough, and, in severe cases, unpleasant lactic and cheese-like notes may be detected.

Cork taint

Among wine faults, cork taint is the most widespread and easiest to identify. The primary culprit is a molecule called trichloroanisole (TCA), although it is not the only one. TCA forms under specific conditions when cork oak trees are infected by the Armillaria Mellea fungus (from the same family as the common honey fungus). This is why the fault is commonly referred to as cork taint.

However, in rarer cases, the fault may stem from microbial contamination of grapes or production facilities. In such instances, the entire wine batch could be affected, not just bottles sealed with contaminated corks.

What does a corked wine smell like? Mostly unpleasant aromas, such as:

- Damp, rotting wood

- Mould and fungus

- Wet cardboard and newspapers

On the palate, the wine feels drying and stripped of its expected flavours, making it unappealing and dull.

US tariffs: here are the Italian wines most at risk, from Pinot Grigio to Chianti Classico

US tariffs: here are the Italian wines most at risk, from Pinot Grigio to Chianti Classico "With U.S. tariffs, buffalo mozzarella will cost almost double. We're ruined." The outburst of an Italian chef in Miami

"With U.S. tariffs, buffalo mozzarella will cost almost double. We're ruined." The outburst of an Italian chef in Miami "With US tariffs, extremely high risk for Italian wine: strike deals with buyers immediately to absorb extra costs." UIV’s proposal

"With US tariffs, extremely high risk for Italian wine: strike deals with buyers immediately to absorb extra costs." UIV’s proposal Meloni: "Tariffs? If necessary, there will be consequences. Heavy impact on agri-food sector"

Meloni: "Tariffs? If necessary, there will be consequences. Heavy impact on agri-food sector" The Government honours the greats of Italian cuisine, from Bottura to Pepe. Massari: "Thank you, Meloni, the only one who listened to us"

The Government honours the greats of Italian cuisine, from Bottura to Pepe. Massari: "Thank you, Meloni, the only one who listened to us"