"The most expensive young wines of Bordeaux were mostly purchased by Irish merchants during the 18th century. These merchants then blended Bordeaux wine with wines from the Rhone Valley and eastern Spain for sale in Great Britain and Ireland. The Irish merchants were aware of the frequent shortages even in the best wines and, by blending them, they responded to the demands of elite British and Irish consumers. Subsequent changes in winemaking, from vineyard to cellar, and the demand for pure wines from customers, would put an end to the practice of blending." The following passage is excerpted from an article written by Professor Charles Ludington, a wine historian, university professor of history, and editor of the Bloomsbury Cultural History of Wine, a six-volume encyclopedia on the history of wine set to be published next year. His area of specialization has led him to analyze how wines have developed into their modern forms and how this has been influenced by soil, climate, geography, tradition, technical knowledge, taxation, foreign policy, fashion, and even gender.

The Irish and Bordeaux production

Professor Ludington's studies began with reading the writings of two important French historians, Paul Butel and Jean-Pierre Poussou, who in their book "La vie quotidienne à Bordeaux au XVIIIème siècle" write: "English and Irish merchants arrived in large numbers between 1720 and 1750, founding many famous commercial houses where their role in trade and especially in wine production was essential: the history of Bordeaux Grand Crus is linked to their presence."

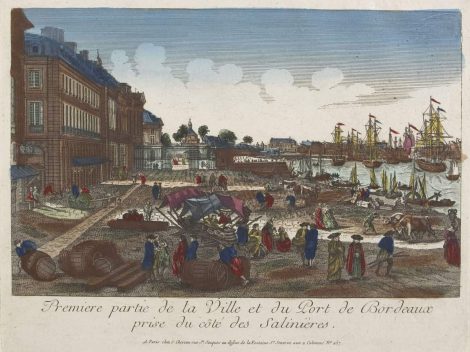

Specifically, the role of Irish merchants was strategic from a commercial point of view because, after purchasing the best local wines, they not only found the right sales outlets but also played an important role in the aging process: because "it was in the merchants' warehouses and not in the Chateau itself that the aging took place." In all this, it must be said that the Irish were not the only merchants present at that time, but rather, in terms of volume, they were surpassed by Germans, Dutch, and Danes. However, what must be recognized is the fact that they were the first to create market outlets for the most expensive wines, perfected aging techniques in their cellars along the Quai des Chartrons, and provided the necessary capital to producers to create wines worthy of their high price.

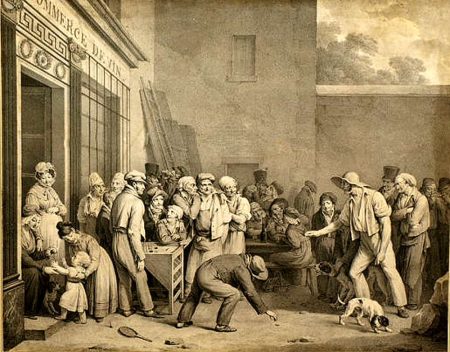

Brawl among Bordeaux winemakers in front of the Chamber of Commerce of the French town. Cover photo: © RMN/Jean-Gilles Berizzi

The success of international blends

Another fundamental element of success attributed to Irish merchants was the practice of blending the best wine productions of Bordeaux with wines mainly from northern Rhone and eastern Spain. This blending, well known to all actors in the industry, catered to the tastes of the English, who at that time were among the main buyers of French wine and, for this reason, contributed to the success of what are still important and historical Chateaux today. A practice, that of blending, very ancient and widespread, so much so that in 1698 in London, a guide for winemakers entitled "In Vino Veritas" was published: many ingenious ways could be found to make "French" and "Spanish" wines with a wide range of ingredients, or to "correct" wines gone bad. This practice was also testified to by the father of English journalism, Joseph Addison, who in an edition of The Tatler in 1709 wrote: "There is in this city a certain fraternity of chemical operators who work underground in holes, caves, and dark retreats, to hide their mysteries from the eyes and observation of men. These underground philosophers are daily engaged in the transmigration of liquors and, with the power of drugs and magic spells, raise from beneath the streets of London the choicest products of the hills and valleys of France. They can squeeze Bordeaux from a plum and extract Champagne from an apple."

Elitist London, All-taking Ireland

The destination of French wines was not the same for everyone. London became passionate about the productions of Haut Brion, Margaux, Lafite, and Latour, which in Great Britain were known by the names of their estates already in the first decade of the 18th century, and consumed all their production alone. Ireland, however, thanks to its lower import tariffs, imported more Bordeaux wine than all of Great Britain combined.

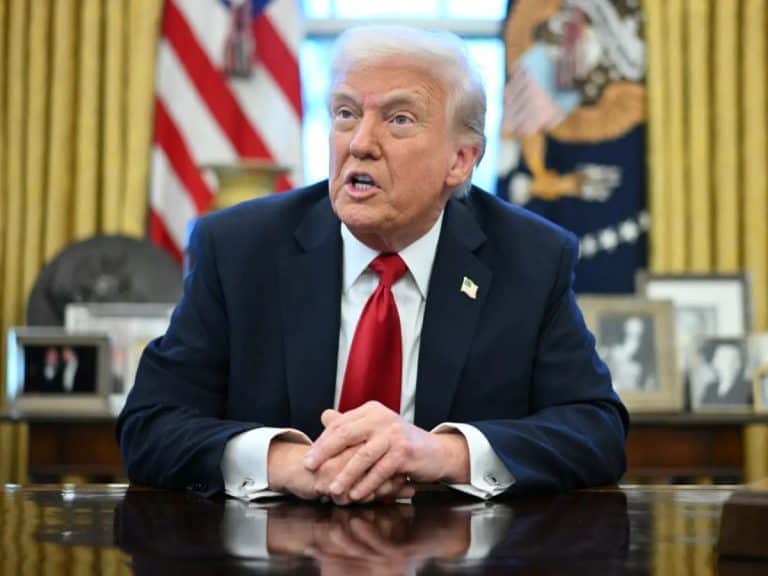

Farewell cacio e pepe in New York. "With tariffs, Pecorino Romano will also become more expensive." The warning from Giuseppe Di Martino

Farewell cacio e pepe in New York. "With tariffs, Pecorino Romano will also become more expensive." The warning from Giuseppe Di Martino Against tariffs? Here are the US foods that could be "hit"

Against tariffs? Here are the US foods that could be "hit" US tariffs: here are the Italian wines most at risk, from Pinot Grigio to Chianti Classico

US tariffs: here are the Italian wines most at risk, from Pinot Grigio to Chianti Classico "With U.S. tariffs, buffalo mozzarella will cost almost double. We're ruined." The outburst of an Italian chef in Miami

"With U.S. tariffs, buffalo mozzarella will cost almost double. We're ruined." The outburst of an Italian chef in Miami "With US tariffs, extremely high risk for Italian wine: strike deals with buyers immediately to absorb extra costs." UIV’s proposal

"With US tariffs, extremely high risk for Italian wine: strike deals with buyers immediately to absorb extra costs." UIV’s proposal