Wednesday evening, pampering. We dine alone in a restaurant in Modena, recommended by a trusted friend. Special feature: it’s not mentioned in any guidebook. At the entrance, a lovely counter with bottles of amaro welcomes you, and the atmosphere is very classic, like a bourgeois restaurant: white tablecloths, wood, and very attentive service. In the dining room, a father and daughter take turns serving, or so it seems from the way they look at each other, first lovingly, then mockingly. After a day of experimental tastings at Cibus in Parma, we want to clear our minds: gnocco fritto, tortellini in broth, and a bottle of Lambrusco di Sorbara, bottle-fermented. The wine list is also stuck in time, with Ca' dei Frati, lots of Piemonte and Toscana wines already seen, and some good regional labels. A breath of fresh air in the choices wouldn’t hurt, but everything is consistent within these walls. Trattoria Bianca has been welcoming customers in Modena since 1947.

The eggplant parmigiana as a welcome appetizer doesn't make a lasting impression, but then the ritual of the gnocco fritto begins. We take a cloud fallen from the sky with our hands - perfectly cooked in the pan - place a slice of culatello on it, and finish with a spread of homemade cherry preserve, the famous Vignola cherries: succulent and slightly tart. They pair divinely, in short, we are delighted. We slow the pace to make everything last a bit longer: a round of ciccioli, a well-aged salami (Spigaroli?), inviting prosciutto, perfect mortadella, and serious culatello with that wonderful cellar aroma that takes us back to some old Trebbiano from Valentini. Boldly, we almost want to ask for seconds, but we desist. It had been a long time since we had eaten gnocco fritto of this level, dry, light, and fragrant.

We get comfortable. "Nonna Bianca started in Pavignane, a small village in Modena, during the War it became the hub for animal distribution, in 1947 the move to Modena," begins the owner Giuseppe Tartini as he seems to dance around the room with perfect timing. The service is old school, attentive and caring, never losing sight of the customer. We are on the outskirts of Modena’s historic center, in what used to be an old farmhouse that also housed animals, with rooms upstairs. "This place has witnessed Italy's history. In the 1950s, people came with their animals and shotguns. In the 1960s, it was mainly frequented by university students, and in the 1970s and 1980s, it was the time of doctors and professors," continues Giuseppe. Among the customers, there’s also a well-known name in the city: Massimo Bottura. "He often comes here to eat, the last time he went into the kitchen and cooked for himself."

The tortellini arrive. The broth is sumptuous, flavorful, and harmonious; adding parmesan would be a crime punishable by three to five years; the pasta is well-filled, with nutmeg gently highlighted. We put aside our critical apparatus, like the thirty seconds less cooking suggested. In front of such a complete broth, we can only immerse ourselves in the atmosphere so far removed from the trends of Trattoria Bianca. At the next table, a couple is tasting tortelloni with ricotta and spinach; someone is already on the second course: beef cheek with mashed potatoes. "Finding staff has become impossible, we rest on weekends, we are closed on Saturday and Sunday." We want to finish with zuppa inglese, Trattoria Bianca is a place for zuppa inglese. After all, several legends place its origin right around here. Yet, for some strange whim or mere sense of guilt, we decide to leave something untried. It will be for the next visit. So, we pay, the average price being 55 euros, and we stroll through the streets of Modena. Beautiful and quiet as we have never seen it.

Meloni: "Tariffs? If necessary, there will be consequences. Heavy impact on agri-food sector"

Meloni: "Tariffs? If necessary, there will be consequences. Heavy impact on agri-food sector" The Government honours the greats of Italian cuisine, from Bottura to Pepe. Massari: "Thank you, Meloni, the only one who listened to us"

The Government honours the greats of Italian cuisine, from Bottura to Pepe. Massari: "Thank you, Meloni, the only one who listened to us" "We must promote a cuisine that is not just for the few." Interview with Massimo Bottura

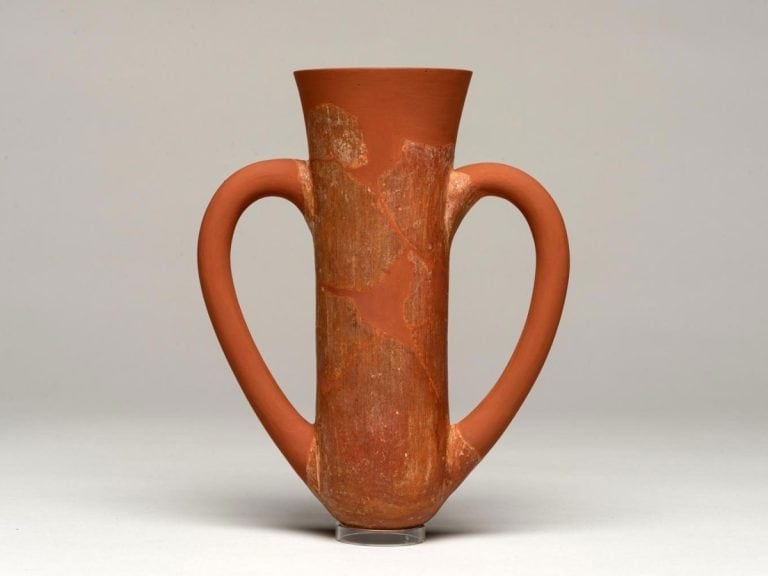

"We must promote a cuisine that is not just for the few." Interview with Massimo Bottura Wine was a drink of the people as early as the Early Bronze Age. A study disproves the ancient elitism of Bacchus’ nectar

Wine was a drink of the people as early as the Early Bronze Age. A study disproves the ancient elitism of Bacchus’ nectar "From 2nd April, US tariffs between 10% and 25% on wine as well." The announcement from the Wine Trade Alliance

"From 2nd April, US tariffs between 10% and 25% on wine as well." The announcement from the Wine Trade Alliance