Over 25% of Umbria’s regional area lies above 600 metres above sea level. This central Italian region is well suited to adapt to new climatic and production scenarios related to wine. On this basis, the Spumantistica Eugubina (Spum.E) project was born, focusing on assessing the environmental, economic, and social sustainability of producing sparkling wine bases in the Eugubino Gualdese Apennine belt. This project, financed by regional RDP (Rural Development Programme) funds, involves the Department of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences of the University of Milan, together with the Semonte and Arnaldo Caprai wineries, with the support of the consultancy firm Leaf. Favourable climatic conditions, such as a reduced frequency of heat extremes, promote the ideal ripening of the grapes. Over the two years of experimentation, sensory analysis of the wines has confirmed the strong potential of this area for producing sparkling wine bases.

Spum.E Project sparkling wines Umbria - steel tanks

The 6-hectare experimental vineyard

The Spum.E studies started with a 6-hectare experimental vineyard planted between 2017 and 2019 with Chardonnay and Pinot Noir (ideal varieties for traditional method sparkling wine production) in San Marco di Gubbio, managed by the Semonte agricultural company (Colaiacovo family) at an altitude between 750 and 850 metres. This vineyard is located on abandoned lands previously used for arable farming and pasture. According to the results presented in Gubbio on Monday, 30 September, the quality of the grapes was found to be optimal and superior to those grown at lower altitudes. The harvest is later compared to the plains, and the water requirements are significantly lower.

Towards an Umbrian sparkling wine district

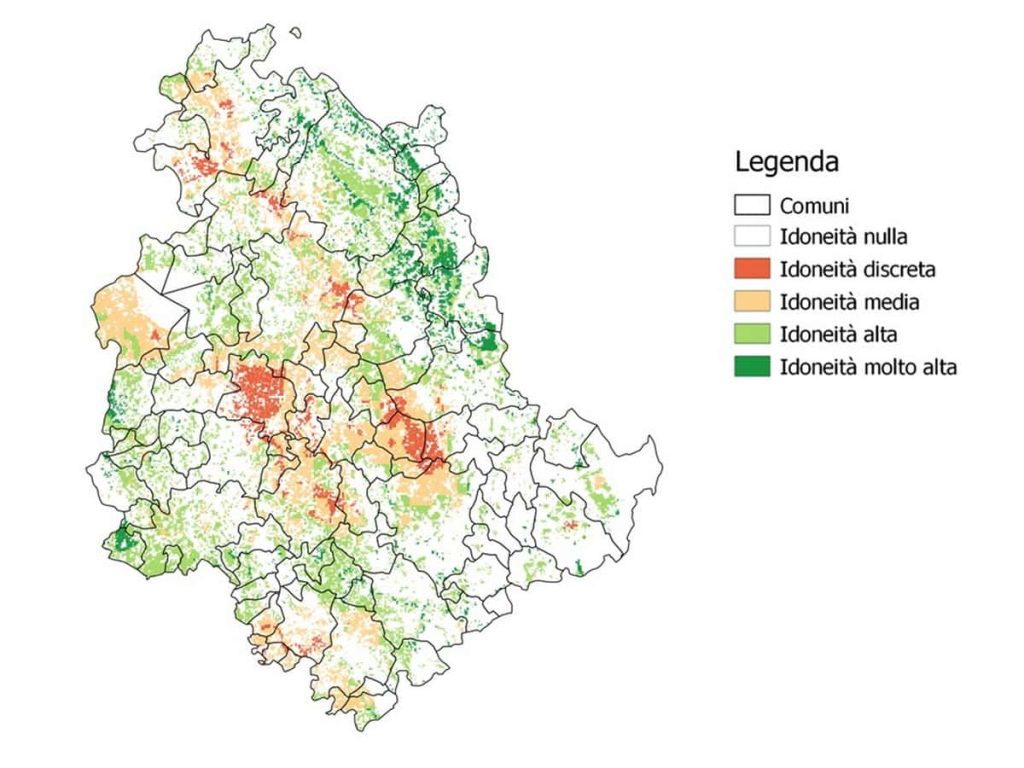

According to the University of Milan, the research data from the Spum.E project could stimulate the creation of a genuine sparkling wine district in Umbria, serving as a virtuous example for other mountainous regions in Italy. “11.3% of Umbria’s utilised agricultural area, with good suitability for vine cultivation, is located in mountainous areas, which have been socio-economically fragile, where new investments could revitalise the rural economy,” explained Chiara Mazzocchi, Associate Professor of Agricultural Economics at the University of Milan. When considering areas with high suitability for vine cultivation from a climatic, hydrological, and soil perspective, the proportion in mountainous regions rises to over 20%. This suggests that these areas may be more suitable for cultivating varieties that require specific conditions to produce grapes ideal for sparkling wine production. “There could be a double enhancement of the Apennine mountain areas: economic and social,” Mazzocchi added.

Spum.E Project Umbria - sparkling wines - vineyard technology

Mapping the municipalities

The research led to a mapping of the municipalities (based on parameters such as thermal stress, evapotranspiration, late frosts, and the Winkler index) that host the most suitable areas for vine cultivation, complemented by an indicator of the socio-economic fragility of the municipalities themselves. This highlights which zones would be most attractive for potential investments. The study demonstrated, through constant monitoring, that the higher-altitude vineyards recorded -40% fewer infectious events of downy mildew and powdery mildew compared to the lower-altitude vineyard for Pinot Noir and -60% fewer for Chardonnay. The new environments would thus be easier to manage from a phytosanitary standpoint. From the six hectares of vineyard, traditional method sparkling wines have already been bottled and will debut at Vinitaly 2025, both for the Semonte company and for the Arnaldo Caprai winery.

Umbria - Spum.E project - Suitability map for sparkling wine grape cultivation (University of Milan)

The Eugubino Apennines like Bordeaux and Alsace

Initial viticultural characterisation of the regions indicates that the high-altitude sites in the Eugubino Apennines have seasonal thermal resources typical of areas known for producing quality white and sparkling wines. Applying the Winkler bioclimatic index (the sum of daily temperatures above which the vine has vegetative and productive activity), the experimental vineyard falls into Viticultural Zone II, similar to cold environments like Bordeaux and Alsace. The lowland zones of the Perugian viticultural area, on the other hand, fall into Zone IV: a warmer climate more suited to varieties like Alicante, Malvasia, Grenache, or Sangiovese for the production of ageing wines. As Gabriele Cola from the Department of Agricultural Sciences at the University of Milan noted, climate change can also be seen as a “great opportunity for viticulture in mountain areas.”

Umbria - Spum.E project - Grape harvest

Revitalising the Apennines

“I believe Spum.E is a very useful project for our region because our Apennines need to be brought back to life,” said Donatella Tesei, President of the Umbria Region. “Spum.E also aims to create business networks to compensate for the small size of agricultural enterprises. The small size of vineyards is no longer sustainable in viticulture,” noted Marco Caprai (Arnaldo Caprai winery). For Giovanni Colaiacovo (Semonte company), the recovery of abandoned mountain areas through the idea of high-quality sparkling wine production “can be a great opportunity for young people, helping them stay in our region and find new, sustainable ways to earn a living.”

The limits of the project

Among the challenges identified for establishing an Umbrian sparkling wine district are the constant depopulation of these areas and the fragmentation of land ownership. According to the University of Milan’s study, businesses struggle to find available or viable vineyard land, as it is often owned pro indiviso by numerous disinterested owners. Hence, legislation that facilitates land consolidation is highly desirable, not just to support viticulture but for mountain agriculture in general. Finally, difficulties also arise from the abolition of replanting rights and the need for supportive measures for mountain viticulture.

Burgundy’s resilience: growth in fine French wines despite a challenging vintage

Burgundy’s resilience: growth in fine French wines despite a challenging vintage Wine promotion, vineyard uprooting, and support for dealcoholised wines: the European Commission's historic compromise on viticulture

Wine promotion, vineyard uprooting, and support for dealcoholised wines: the European Commission's historic compromise on viticulture A small Sicilian farmer with 40 cows wins silver at the World Cheese Awards

A small Sicilian farmer with 40 cows wins silver at the World Cheese Awards Women are the best sommeliers. Here are the scientific studies

Women are the best sommeliers. Here are the scientific studies Where to eat at a farm stay in Sicily: the best addresses in the Provinces of Trapani, Palermo, and Agrigento

Where to eat at a farm stay in Sicily: the best addresses in the Provinces of Trapani, Palermo, and Agrigento