The caper, the flower bud of the Capparis spinosa, is a small, savory counterpoint capable of making a difference in recipes like escarole pizza, vitello tonnato, spaghetti alla puttanesca, or a simple summer salad. When the buds open, they reveal white flowers with a cluster of fuchsia-purple stamens in the center, which, clinging to ancient walls, rocky cliffs, and dry stone walls, create a spectacular sight.

Capers, what a plant!

The caper is not the only product of this shrub found throughout the Mediterranean basin, from Spain to the Arabian Peninsula, including southern Italy, our major islands, and North Africa. There is the cucuncio, the fruit of the caper that forms after the flower blooms, a long, firm, and fleshy berry ideal as a finger food for appetizers and starters. There are the leaves, with the dried version being a crunchy, light, and fun snack perfect for the classic aperitif. Forget about bagged chips! La Nicchia, a historic caper processing company in Pantelleria, completes the entire supply chain from the soil to the jar, working even at night, and offers all the products of the plant: the caper itself, protected by a PGI since 2010, the cucuncio, the leaves, and even the sprouts. Based on these core products, they create a variety of items in different lines: in salt, oil, vinegar, dried, as spreads, and featured in a rich range of specialties alongside other ingredients (oregano, olives, sun-dried tomatoes, almonds, anchovies). Completing their range are Pantelleria oregano, zibibbo raisins, various pâtés and pestos, orange marmalade, and jams with island flavors, and Passito di Pantelleria.

The history of La Nicchia in Pantelleria

The farm with the caper processing facility, the historic site of this rural Pantelleria reality, is located in the Scauri district and was established in 1949 by Antonio Bonomo and Girolamo Giglio. It was later passed on to the founders' children and then to Gabriele Lasagni, the current owner of what is now one of the jewels of caper production in the Black Pearl of the Mediterranean. "To complete the supply chain," explains Lasagni, "in 2010 we purchased the brand and laboratory from Gianni Busetta (owner of the La Nicchia restaurant), in Via Stufe di Khazzén; next to it, we set up the Caper Museum." The company's flagship product is the caper, offered in every size, type of processing, and preservation: small, medium, and large, in sea salt, white wine vinegar, extra virgin olive oil, crunchy, powdered, PGI Pantelleria capers, organic (only from the company's land), up to "space" capers, meaning freeze-dried "for space missions," extraordinarily brittle, ideal for unusual aperitifs and a – Lasagni assures – gastronomic experience. This experience is undoubtedly guaranteed by the PGI capers, tiny and compact, with a wonderful vegetal and briny aroma reminiscent of the sea, sun-scorched rocks, and sculpted by wind and salt, wild bay leaves, and rosemary.

Are the lleaves of Capparis Spinosa the future of Production?

But the real surprise is the leaves. "They are an excellent condiment," explains La Nicchia's owner, "a complete product: flavor, texture, geometry." Those in salt are "loved by starred chefs." Those in extra virgin olive oil are ideal for seasoning and garnishing dishes, or for frying in batter. The crunchy leaves are perfect for crumbling into soups, broths, and consommés, and especially as chips for aperitifs, a formidable alternative to bagged chips: tastier, healthier, and truly – literally – lighter. "The caper leaf is not part of the island's tradition, it is a new product born from the need to optimize caper production costs. Today, you can even profit from this part of the plant," adds Lasagni. "Our slogan is 'we are building the future of the caper.' But I see this future as grey, there are many issues yet to be resolved."

Climate change and labor

The problems surrounding this rustic product, rich in flavor and nutraceutical virtues due to its high quercetin content, are many and complex. "We do not use aromas or preservatives, everything is very natural and simple. But in reality, producing in Pantelleria is very complicated," explains Gabriele Lasagni. "In the field and the laboratory, mechanization is extremely difficult: in the caper field, we have to use hand-pushed tractors, there is no water, and the wind tears everything up so no greenhouses. We are at the mercy of nature and weather events." Another issue is the average age of the producers, which is very high. "Young people are not incentivized to do this work. Small farmers in Pantelleria collect 50-100 kilos of capers a year and are not interested in undergoing PGI controls. We cover the difference, but for such small quantities, a few hundred euros do not impact the family economy." Here, the problem of labor arises. "It has been an issue for over 20 years. I had sought people in Morocco, a major caper producer," recounts Lasagni. "I found five ready to come to Pantelleria to work on our farm. We would have paid for the trip, provided food and lodging. They were interested. This job would have been an economic resource for themselves and their families, with a monthly salary of 1,500 euros without expenses, they could have saved money to send back to Morocco. Then, when everything was ready to bring them here, there were bureaucratic issues...".

The processing is also challenging. "There is no specific equipment for capers like there is for wine, oil, or tomatoes. Working with a salted raw material, we use steel, which requires constant maintenance. In Conegliano, we bought a vegetable washing tank and adapted it for capers, investing money, hours, and effort. After less than two years and an investment of 65,000 euros, it is almost unusable: the brine damages even stainless steel AISI 316."

Caper production in 2023

Last but not least, climate change, which does not spare Pantelleria and exacerbates the drought, a long-standing major issue for the island. "The 2023 campaign yielded 42% less production, but not just because of the drought," specifies Gabriele. "The caper is a plant that grows in dry farming. Most of the land goes into production in late May-early June. Last year, in February and March, months when rain is usually expected, the temperatures were summer-like. In May and June, when it should be very hot, temperatures were not so high, so during the crucial period, the plants were dormant. Then in July, they started growing, and something was harvested in September, but most was lost."

2024 is even worse, worsening the extreme fragility of Pantelleria's agricultural ecosystem. "The days around San Giovanni are usually the peak caper harvest, but this year the situation is dramatic, both for capers and especially for oregano: production is zero. What will be the agricultural future of Pantelleria, particularly for capers?" Perhaps it's in the leaves. "Due to climate whims, the plant's flowers struggle and do not reach the bud stage, but the leaves grow lush and fleshy. Their harvest is an additional incentive to sustain a precarious situation and a strenuous production," concludes Lasagni, "especially for farmers who are undecided whether to continue or abandon their land."

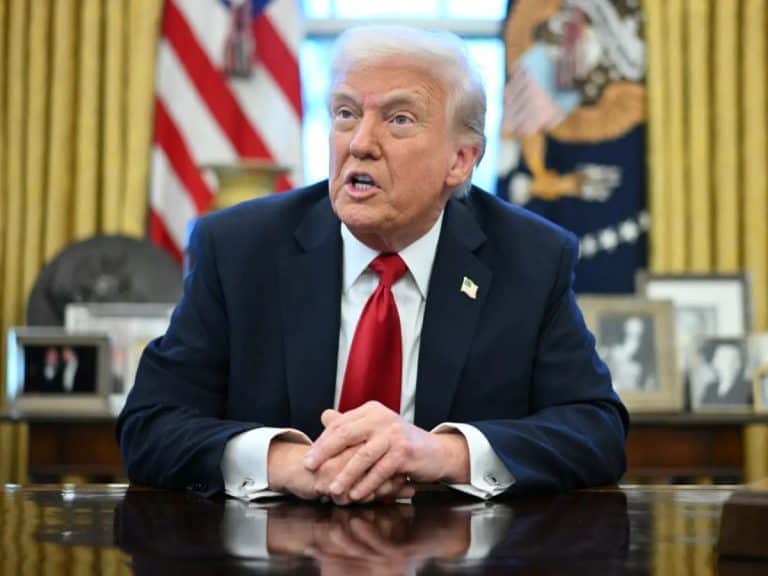

Farewell cacio e pepe in New York. "With tariffs, Pecorino Romano will also become more expensive." The warning from Giuseppe Di Martino

Farewell cacio e pepe in New York. "With tariffs, Pecorino Romano will also become more expensive." The warning from Giuseppe Di Martino Against tariffs? Here are the US foods that could be "hit"

Against tariffs? Here are the US foods that could be "hit" US tariffs: here are the Italian wines most at risk, from Pinot Grigio to Chianti Classico

US tariffs: here are the Italian wines most at risk, from Pinot Grigio to Chianti Classico "With U.S. tariffs, buffalo mozzarella will cost almost double. We're ruined." The outburst of an Italian chef in Miami

"With U.S. tariffs, buffalo mozzarella will cost almost double. We're ruined." The outburst of an Italian chef in Miami "With US tariffs, extremely high risk for Italian wine: strike deals with buyers immediately to absorb extra costs." UIV’s proposal

"With US tariffs, extremely high risk for Italian wine: strike deals with buyers immediately to absorb extra costs." UIV’s proposal